When times are good, being a country director for Peace Corps may be the best job in foreign affairs. This has not been such a time.

As told to Steven Boyd Saum

Photo: Vyshyvanka Day, when schoolchildren don the traditional Ukrainian shirt — and here, pose as one. Photo by Kevin Lawson

Kim Mansaray | Country Director, Mongolia

JANUARY AND NEWS OF THE VIRUS came out in China. Mongolia says we’re not sending kids back to school. Our winter break became endless winter break. Then the virus exploded in China, and Mongolia went on hardcore lockdown — borders and flights.

From time to time in Mongolia, there’s an outbreak of something, then a quarantine — fairly routine. That was on our minds: Watch how this plays out. The clincher was when flights from Seoul were canceled. I talked to the embassy and said, If people need to be medically evacuated, we’re not gonna be able to get them out.

The farthest part of the country is normally a 40-hour bus ride. It took five days with help from embassy cars to caravan all Volunteers back in. And of course, because it’s Mongolia, there was a blizzard.

Volunteers just a few months in were put on administrative hold. Then, in mid-March, Washington moved everybody to Close of Service. My Volunteers were giving me grief. I said, I get your frustration and your anger. But this is unchartered territory for Peace Corps.

Should Volunteers return? Are we valued? How do we reset this for the country? They’ve heard communities say: “We want the volunteers back as soon as possible.”

Mongolia on horseback. Photo by Antonio Mercatante

Fast forward to June: Our staff in Mongolia have been out and about and in the countryside, visiting potential sites, picking up luggage that Volunteers left behind. And making honest assessments: Should Volunteers return? Are we valued? How do we reset this for the country? They’ve heard communities say: “We want the Volunteers back as soon as possible.” There’s a real connection. Volunteers are staying in touch with communities. Mongolia is incredibly wired; they use Facebook for everything.

Here, they see what’s happening in the U.S. Three, four days a week, people come in my office and ask: “What is going on?” Diplomatically I say, “Our democracy is right out there for you to see. It’s messy and it’s ugly, and it’s been tough.” But they know what the Volunteers have been doing in communities. That resonates here. Mongolia has an incredible commitment to not allowing community spread of COVID-19. They understand why the Volunteers left. And they’re uniformly asking, “When are they coming back?”

Ukraine: The winter walk to school. Photo by Kevin Lawson

Michael Ketover | Country Director, Ukraine

FRIDAY THE 13TH of March, still only three cases confirmed in Ukraine. The Ukrainian government acts quickly: bans foreigners from entering, effective in 48 hours; 170 border checkpoints closed. We go to alert stage. Overnight a nationwide lockdown is imposed. We activate standfast. Saturday morning, airports close. Time to evacuate.

I was in Kryvyi Rih at a training with Volunteers and Ukrainian partners; took the 7-hour train back to Kyiv Saturday morning. Peace Corps in DC agrees on evacuation, finds a charter plane from Jordan, to arrive Monday. PC Ukraine, largest post globally, had 274 Volunteers serving; a large group completed service earlier that winter. Imagine doing this with the full 350 PCVs, I thought. We tell all Volunteers to get to Kyiv by Sunday night; they do. We get them to the airport — which is closed, skeleton staff. Still only seven cases in Ukraine. We wait. Flight delayed several times, then, about midnight, canceled. Hotels were closing. We found rooms in three; staff bought PCVs water and food, since restaurants were closing.

Tuesday’s charter: delayed then canceled. The company hadn’t arranged landing fee payment, secured a ground crew, etc. Wednesday: flight delayed several times, then canceled last minute. Despite support from the U.S. Embassy in Amman, the government of Jordan wouldn’t let the plane leave because of new COVID restrictions. Wednesday night I propose asking the U.S. military if we can fly Volunteers out on a military aircraft. And I talk to the CEO of a small startup airline in Ukraine interested in making its first flights to the States.

Thursday, 19 cases. We’re getting inquiries from congressional offices about concerned Volunteers’ parents: What’s going on? Thursday: delays, cancellation. Peace Corps HQ locates a different charter company from Spain. I insist on being put directly in touch with them. Thursday night 10:30 p.m., wheels up Madrid. We move PCVs in six different buses, with police and Regional Security Officer escort since it is now illegal to gather more than 10 people. At Kyiv airport, there’s a technical issue: They can’t issue or print boarding passes. So airport staff write them out by hand. Check-in took 10 hours. Friday morning, 6:20 a.m., plane departs. Kyiv to Madrid to Dulles to homes of record.

The real unfinished business is Goal Two: deep relationships Volunteers have been establishing, person-to-person. Friendships and peace-building are the essence of Peace Corps — even more so in a place like Ukraine, a geopolitical epicenter.

When I say we it’s the incredible PC local staff. Many had been through evacuation before, in 2014. I managed an evacuation in Papua New Guinea years ago but much less hectic and with only 22 PCVs. This time I was managing it from my Kyiv apartment — Friday I received notice that I had to self-quarantine because I had returned from Europe within the past two weeks. So I’m calling every Volunteer I could to say goodbye during that overnight check-in. During all this we’re posting on social media every day. This was time for gratitude: to counterparts and local staff, host families and government ministry partners, superstar volunteer wardens and our dear Volunteers. I encouraged the Volunteers to stay in touch with counterparts, work remotely if they could — on grant proposals, civic education with youth, English clubs on Zoom, anything; 100 evacuated PCVs have put in nearly 2,000 hours of virtual volunteering already.

Staff here have restarted programs before. They are working hard even without PCVs in country to maintain meaningful contact with counterparts. They know how to do it.

As for unfinished business, there’s goal one for Peace Corps — work Volunteers do in teaching, youth and organizational development. That’s important, but the real unfinished business is Goal Two: deep relationships Volunteers have been establishing, person-to-person. Friendships and peace-building are the essence of Peace Corps — even more so in a place like Ukraine, a geopolitical epicenter. When I talk to counterparts, local staff , and Volunteers, I emphasize this. Counterparts love it: Work, yes, but also inviting Volunteers to birthday celebrations, funerals, and weddings, berry picking in the forest — that makes this experience unique and awesome. The Third Goal, that’s unfinished: making America less insular — helping Americans appreciate the realities of life in different places. Those three goals, equally important, are the beauty of our wonderful organization.

Ghana: Gathering for a baby-naming ceremony. Photo by Meg Holladay

Gordon Brown | Country Director, Ghana

IT HAD ALREADY BEEN A TOUGH YEAR for us in Ghana. In October, one of our Volunteers, Chidinma Ezeani, died after a tragic gas accident in her home. Thirty-nine Volunteers had to be relocated out of the northern part of the country because of security concerns across the border. Peace Corps Niger is closed because of security; Burkina Faso, too.

Then the virus: by March, regular emergency meetings at the embassy. Countries started closing, restricting airspace. It looked like Ghana was going to close — within the span of probably half a day. Sunday night, they said, Go in tomorrow and tell all 80 Volunteers to move. How fast can you do it? Now, our organizational culture in Peace Corps is not like the military: Here are your orders, execute. But in a moment like this, it has to be: Do this now — like now now.

My former boss used to say, “Being Peace Corps country director is the best job in foreign affairs.” I started as country director in Benin in 2015, then in Ghana in 2018. Along with the joy of the work also sometimes comes tragedy. So how do you be the best when times are the worst? Executing an evacuation takes massive logistical effort and focus. It was us all together — the Volunteers and the agency — that were able to make that happen. We had planes that were supposed to show up that didn’t. When we did get a plane — well, it had been a tough week for me personally, too. My wife had injured a muscle in her leg. So it’s 80 Volunteers, my wife in a wheelchair, our 3-year-old, our 7-year-old, all of our luggage — you can’t make up that level of difficulty. It was level 10.

Then there’s this big question: How do we stay true to the original mission — the philosophical underpinnings — and make the modern iteration of the Peace Corps? It takes courage to stand up and say, “I believe in being committed to something.”

As hard as this has been, here’s something that I think has become clear to a lot of the Volunteers: You don’t stop being a Volunteer just because you’re no longer at your site in a country. We’ve got the technology now that allows many Volunteers to be connected all the time. But that doesn’t change the fact that you need to be able to communicate with people in front of you. You need to be able to read people’s emotions and speak with them in a way that is that being empathetic to what they’re going through.

We have to wrestle with what Peace Corps means in the modern world. How does it remain relevant? Ghana is the oldest Peace Corps operation in the world. It started in another era; 1961 was the year of Africa, when some 20 nations became independent. In 1960, the Prime Minister of England, Harold Macmillan gave a speech about “the wind of change” blowing through the continent.

In Ghana, one question is: How do we keep Peace Corps from seeming like a piece of old furniture? It has always been there. Kwame Nkrumah is always a big hero. John F. Kennedy is a big hero. America and Ghana have always had a close relationship. But how do we renew excitement among the government and people of Ghana — to understand that these Volunteers who are capable and tech-savvy, involved and committed, have something to offer? It’s a welcome challenge.

For the agency this is a massive undertaking in terms of charting the way forward: what the focus areas are going to be, what the footprint is going to be — what sectors, sizes, countries? All of that is going to have to be decided on an individual basis. As I like to tell Volunteers: Any victory lies in the organization of the non-obvious.

Then there’s this big question: How do we stay true to the original mission — the philosophical underpinnings — and make the modern iteration of the Peace Corps? It takes courage to stand up and say, “I believe in being committed to something.”

Morocco: Girls’ hiking expedition. Photo by Gio Giraldo

Sue Dwyer | Country Director, Morocco

WHEN WE STARTED an in-service training there were maybe two cases in Morocco — a country of 35 million. But come Friday morning, March 13, I don’t like where this is going. They shut down flights to Italy, are talking about shutting down flights to France — our primary means of getting out. We cancel the last few days of training. We send Volunteers back to their sites, put them on standfast.

Saturday morning, I call the Deputy Chief of Mission at the embassy and tell him I think I have to get Volunteers out; if we have to med-evac someone, we’re in trouble. We’ve got 183 Volunteers and Morocco is the size of California. For some Volunteers it takes two days to get back to site; they get a day to pack, say goodbye. In Rabat I figure we’ll have three days for a program to wrap things up. The embassy says you’ve got until next Saturday … then Thursday … then Wednesday. OK, here we go. The Moroccan government keeps moving the time when we can fly. I realize, as this is happening, that I still have some muscles working from my humanitarian aid days; I evacuated NGOs out of Liberia in 1999 during the civil war.

A lot of Volunteers email me saying, “Please don’t send us home, we want to be here in solidarity with the Moroccans.” But they come. Some have problems getting back to Rabat — harassment on buses, people saying foreigners brought in COVID. So our Moroccan staff charter buses and send them out to consolidation points.

This has been traumatic for Moroccan communities that had their Volunteer stripped from them. For the Moroccan staff, for the American staff. But it’s also a time when all of us can reflect on what we’re doing well, what systems need to be strengthened. We get a chance to start fresh.

At the airport we have a charter flight with maybe 225 seats for Volunteers only. They start calling: “My grandmother and my mother are here — and the airport’s closed.” So we say yes. Then: My parents, my aunt , my brother. So we have to finish what we started. Thursday at 2 a.m., the plane takes off. Second-year Volunteers knew they were being COS’d. First-year Volunteers were told they were on administrative hold. While they were flying that changed. They got off the plane, they got a different message. That was soul-crushing.

Peace Corps Morocco is one of the oldest programs, and currently the only one in the Arab world. We’re the largest youth development program; it’s our sole area of focus. The evacuation was a huge earthquake with all the aftershocks. And it’s not just for Volunteers. We’ve got host families calling and saying, “I can’t reach my volunteer daughter, son” — because their number changed. “When we see what’s happening in the United States, we’re really worried. Are they OK?”

This has been traumatic for Moroccan communities that had their Volunteer stripped from them. For the Moroccan staff, for the American staff. But it’s also a time when all of us can reflect on what we’re doing well, what systems need to be strengthened. We get a chance to start fresh. If we were to do training in a completely different way, what would that look like? So this is an important time for innovation and rethinking our models

.

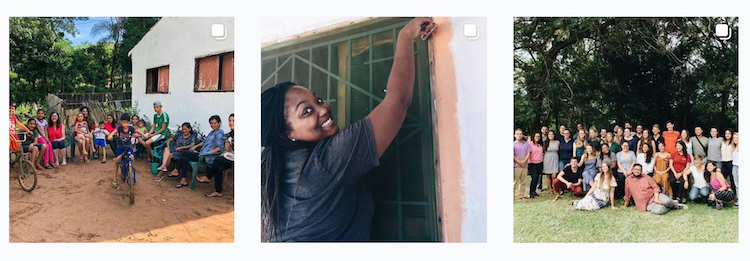

Paraguay: Scenes from an Instagram feed before evacuation

Howard Lyon | Country Director, Paraguay

WE KNEW THE VIRUS was on its way, burning across the world. It was going to hit Paraguay sooner or later. Infections had begun in Brazil. At the time we thought maybe we could ride out the storm. But the world was getting stormier. Then with the infections in the United States, we began getting inquiries from parents: “Where’s my daughter?” “What’s your plan?” I had traveled to the region called the Chaco — very isolated and hot, and there was the theory that the virus doesn’t like heat. That was my last trip to the field.

By March 15 it was very serious. A strange morning, overcast, leaves beginning to fall; autumn was just beginning. Walking to our office I was the only person on the street — a major thoroughfare in Asunción. People were beginning to stay at home; the government was making noises about curfews. We started preparing for lockdown. This happens to be my second evacuation in two years; in 2018 we evacuated Nicaragua — though under very different circumstances. But it’s heartbreaking to take Volunteers from their communities.

Sunday night we got the call. We had a week to get 180 Volunteers out. Paraguay is an inland island, surrounded by Brazil, Argentina, and Bolivia. Politically it was isolated for years. You fly to North America through São Paulo, Buenos Aires, or Santiago, and then another connection. We got word that Panama, a central hub to get people to the U.S., was going to close. By Wednesday word was the airport in Asunción might close. We even had a group on a bus to the airport when our travel agency canceled our tickets. So we brought people back to their hotel. Saturday, we got a chartered flight, our last large group. Lockdown began the night before; we weren’t even allowed to leave our homes to say goodbye to them. So it’s all WhatsApp, and we’re calling, we’re saying goodbye in other ways.

THREE MONTHS LATER, Latin America is being harder hit. Volunteers I speak to express gratitude to the country, sadness for leaving their communities here, but also gratitude for being close to their families in the U.S. during this time. In Paraguay, we were on strict lockdown the first month, and that helped. In Peru and Ecuador, it’s a terrible situation. Brazil is horrific. Here the population is about 7 million. We’re around 1,300 cases now; there have been 12 fatalities.

Our staff have been talking to community members and counterparts. They want everybody back. But it’s going to be a different world. In Paraguay, kissing and hugging are a big part of the culture; so is sharing food, or drinking tereré out of the same gourd or straw. That will change. If the opportunity presents itself to return Volunteers, they will be well received by their communities. But we’re going to have to think about how you go in as the foreigner who has been in a country with such high infection rates.

Another crucial factor: New and returning Volunteers alike have not only lived through an extraordinary world health catastrophe, but the recent murders of Black Americans, which are a consequence of centuries of racism, have brought another time of protest and a time of reckoning. All of us as individuals and as organizations have to look within ourselves and truly recognize that this situation — the mistreatment of people because of race — is the heritage of our country. We have to deal with it. It doesn’t mean everybody’s bad, doesn’t mean everybody’s good. It just means we’ve got to live together.

The purpose of the Peace Corps is to break down any kind of barrier to understanding each other. This is something everybody in the world is facing. This is not one region. This is not one country. This is not one class.

When the Black Lives Matter movement began a few years ago, there were repercussions in the Peace Corps. Some wanted the agency to answer hard questions. This is now even stronger and more tragic. The economy and unemployment, the illness and who it affects most, and the reckoning with justice: It’s an extraordinary time. So our staff need to be compassionate and understanding.

I haven’t been to every country in the world, but I’ve seen a bunch. And I don’t know of any non-racist country, especially in this part of the world. Africa was colonized by Europeans who, to do what they did, dehumanized native populations. That curse has been with us ever since. In this part of the world, when we talk of Europeans — the Spanish and the Portuguese — this conquest was very violent. These nations were born in violence, but they’re trying to reckon with it.

The purpose of the Peace Corps is to break down any kind of barrier to understanding each other. This is something everybody in the world is facing. This is not one region. This is not one country. This is not one class. Every one of us is facing uncertainties — and we’re social distancing, losing human contact. I hope compassion is what we learn out of all this. It’s not just, OK, lights are on again.

As I said to the last group flying out, when I called and they put me on speakerphone: We truly love you guys. We love you Volunteers.

This story was first published in WorldView magazine’s Summer 2020 issue. Read the entire magazine for free now in the WorldView app. Here’s how:

This story was first published in WorldView magazine’s Summer 2020 issue. Read the entire magazine for free now in the WorldView app. Here’s how:

STEP 1 – Create an account: Click here and create a login name and password. Use the code DIGITAL2020 to get it free.

STEP 2 – Get the app: For viewing the magazine on a phone or tablet, go to the App Store/Google Play and search for “WorldView magazine” and download the app. Or view the magazine on a laptop/desktop here.

Thanks for reading. And here’s how you can support the work we’re doing to help evacuated Peace Corps Volunteers.