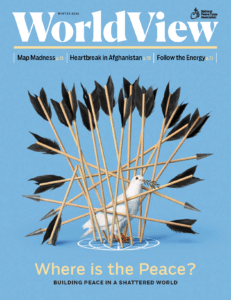

Building Peace in a World at War

by Robert Nolan

Winter 2023-24 Issue Cover, by Doug Chakya

Those concerned with the state of global peace might be forgiven for succumbing to a melancholic, even defeatist point of view given the events of the past few years. The world is experiencing the highest level of violence since World War II, with armed conflicts simmering, enduring, or raging in Ukraine, Ethiopia, Yemen, Afghanistan, and Israel/Palestine, to name just a few. In 2022, more than 2 billion people lived in conflict-afflicted areas, and 110 million were displaced by violence, according to the United Nations. And the 2023 Global Peace Index, one of the most reliable measures of current levels of war and peace, states that the total number of conflict-related deaths rose last year by an astonishing 96 percent.

“With the world in a moment of flux, constraints on the use of force, never that strong, are crumbling,” says Comfort Ero, president of the International Crisis Group, one of the world’s leading orga- nizations committed to preventing and resolving deadly conflict. “More leaders worldwide believe they can get away with pursuing their interests militarily, vanquishing foes rather than bargaining.”

It wasn’t supposed to be this way.

After the mass casualties and destruction of the Second World War, the victors came together to create institutions and frameworks meant to help prevent future wars, mediate conflicts, and rebuild postwar societies. For decades, such entities—the United Nations, the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, NATO, and later the European Union—helped to at least mitigate the kinds of mass atrocities seen in the wars of the 20th century.

But this global peacebuilding infrastructure, which has always had its cracks, now seems to be undergoing a spectacular collapse. “We are living in a period of de-civilization, and we’re watching it unfold on television,” said Hina Rabbani Khar, Pakistan’s former minister of foreign affairs and an outspoken advocate for human rights, at the Paris Peace Forum, an international conference of political leaders and civil society representatives held last fall. She accused global powers and institutions committed to reducing global conflict of “using the language of peace to promote war. We think the world has ears but not eyes.”

Can the foundations of what has come to be called “peacebuilding” be rescued now, when they may be needed most?

The word “peacebuilding,” which encompasses global efforts in conflict prevention, conflict resolution, and post-conflict reconstruction, is relatively new. It was coined in 1975 by Johan Galtung, a Norwegian sociologist considered by many to be the founding father of peace and conflict studies. Since then, the term has been embraced as shorthand for the work done by both scholars and practitioners in multiple fields related to peace. This work largely rests on the following eight indicators, identified by the Institute for Economics and Peace and known as the Pillars of Positive Peace: Well-functioning government; sound business environment; equitable distribution of resources; acceptance of the rights of others; good relations with neighbors; free flow of information; high levels of human capital; and low levels of corruption.

“We are living in a period of de-civilization, and we’re watching it unfold on television” — Hina Rabbani Khar, Pakistan’s former minister of foreign affairs

Key players in peacebuilding can generally be grouped into three categories. Multilateral institutions such as the United Nations, whose charter declares that “All Members shall settle their international disputes by peaceful means in such a manner that international peace and security, and justice, are not endangered,” make up the first and perhaps most prominent group. Individual states operating unilaterally also play a key role in peacebuilding. In the U.S., such efforts are usually managed by governmental agencies like USAID and the Department of State, and Peace Corps, though its role is not as widely acknowledged. Civil society can be seen as the third player in peacebuilding, attending to a variety of issues specific to different regions, countries, and areas of focus.

MULTILATERALISM IS FAILING

Since its founding in 1945 as the largest multinational organization in history, the United Nations has been highly political. Its most powerful body, the Security Council, consists of five postwar powers—the United Kingdom, France, the U.S., China and Russia —each with the ability to unilaterally veto any resolution related to global conflict. Despite repeated calls for Security Council reform, this configuration is unlikely to change anytime soon. Whether condemning Russia for its invasion of Ukraine or censuring Israel for its response to Palestinian terrorist attacks, the Security Council frequently sits frozen as the world’s most terrible conflicts rage. The General Assembly, which has no mandate to enact enforceable resolutions, as the Security Council does, often votes to condemn atrocities committed by member states—though these votes tend to be driven by current political alignments.

“The more they meet, the less they agree,” said Ghassan Salamé, professor emeritus of international relations and the former dean of the Paris School of International Affairs at Sciences Po, in a panel discussion at the Paris Peace Forum last November. “It’s not revival the U.N. needs, it’s resurrection.”

Of course, many U.N. organizations, including the Department of Peace Operations, the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees, UNICEF, the World Food Program, and the U.N. Development Program, work tirelessly in conflict-afflicted regions worldwide to support peacebuilding. And last year, U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres announced a major new initiative, A New Agenda for Peace, which calls on member states to prioritize conflict prevention rather than intervention, and emphasizes the need to bring new partners and ideas into peacebuilding efforts.

Other efforts, such as a Peacebuilding Commission created in 2005 to support “peace efforts in conflict-affected countries,” have, at the very least, symbolized the U.N.’s commitment to its charter. “The idea of prevention that animated the creation of the Peacebuilding Commission remains more urgent today than it did almost 20 years ago,” says Stephen Del Rosso, senior director of the International Peace and Security program at Carnegie Corporation of New York, which funds major peacebuilding efforts, especially in Africa. “Although the Commission may not have met all of its initial expectations, it continues to serve as an important bulwark against the slide toward conflict in some of the world’s most vulnerable countries.”

THE BUSINESS OF PEACEBUILDING

It’s not just multinational organizations that are failing. Unilateral approaches in the peacebuilding repertoire are also in need of refinement.

Shifts in global power dynamics, particularly the rise of China and the growing popularity of authoritarian regimes worldwide, threaten the United States’ de facto role as the country the world turns to when wars need settling and peace needs to be maintained.

Shifts in global power dynamics, particularly the rise of China and the growing popularity of authoritarian regimes worldwide, threaten the United States’ de facto role as the country the world turns to when wars need settling and peace needs to be maintained.

America’s credibility as a peacebuilder was dealt a major blow by its 20-year war in Afghanistan and the controversial invasion of Iraq in 2003. A wavering commitment to global peace in the face of domestic political division has further eroded international confidence among allies and enemies alike in the ability for the U.S. to project power in the name of peace. “Domestic politics is the starting point for foreign policy, and when those who are champions of certain principles like democracy and rule of law that we normally rely on to do international peace and security are themselves in crisis, it leads us to this moment of fragmentation,” says Ero, of the International Crisis Group. “This, in turn, has left a deficit in unilateral efforts to foster peace, allow- ing new players which don’t necessarily espouse the same ideals as the U.S.—think China, the United Arab Emirates, and Saudi Arabia—to project their own interests in conflict-ridden regions.”

Driven by these new dynamics, the U.S. government is starting to rethink its foreign policy around peacebuilding. New initiatives across agencies, including the Department of Defense, Department of State, and USAID, are undergoing strategic review processes not only internally, but in cooperation with other core peacebuilding entities, including multilateral organizations and NGOs.

In 2020, Congress quietly passed the Global Fragility Act, aimed at increasing funding to deal with violent global conflicts; it was signed into law by President Donald Trump. The Biden administration recently announced where the resources allocated by this new law will first be deployed; the list includes Haiti, Libya, Mozambique, Papua New Guinea, and coastal West Africa (Benin, Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Guinea, and Togo).

USAID has also recently launched what Assistant to the Administrator Robert Jenkins calls “the largest reorganization in our history through the creation of the Bureau for Conflict Prevention and Stabilization,” which he now leads. “About 75 percent of the countries that USAID works in are affected by violent conflict, so we’ve doubled down on increasing partnerships with the peacebuilding community,” Jenkins said in a recent interview. “I like to say that USAID is back in the peacemaking business.”

Jenkins says new funding resources, such as $60 million allotted for the Complex Crises Fund, will allow USAID to be more nimble in its peacebuilding efforts, especially those in local communities located in conflict-afflicted regions. That includes West Africa, where jihadist elements threaten U.S. security interests. “How do we help bring communities together with their respective governments and [help them] to be resilient against outside forces?” Jenkins asks. “We’re working to try and craft a new future, so when the guy from, say, Burkina Faso comes into a village with his motorcycle and gun, he doesn’t find folks that want to join him, but who want to repulse him.”

GRASSROOTS RUN DEEP

One area where the foundations of peacebuilding remain strong is within civil society. Local NGOs working on a wide spectrum of peace-related issues are a critical pillar in conflict prevention, resolution, and rebuilding, Ero says. “Their contributions are diverse and include acting as mediators, facilitators of dialogue, bridge builders, and researchers.” Furthermore, she says, “International NGOs play a slightly different role. They can give money and resources to help the local NGOs to carry out their work. They can also make connections for the local NGOs to get their voices heard on the international scene, like the U.N., the European Union, or the African Union.”

“Peace Corps really is, fundamentally, a peacebuilding organization” — Chic Dambach, former president of the Alliance for Peacebuilding

While Peace Corps, a federal U.S. agency that also conducts grassroots development, might not fit neatly into any one of these three broad categories, Volunteers have undoubtedly been engaged in peacebuilding efforts since long before the term itself came into fashion.

“Peace Corps really is, fundamentally, a peacebuilding organization, but the term didn’t even exist when the Peace Corps was created,” says Chic Dambach, former president of the Alliance for Peacebuilding and president emeritus of National Peace Corps Association. “Peace Corps doesn’t do conflict resolution. It can’t and it shouldn’t. What it really does is peacebuilding. Peacebuilding is putting in place the systems, attitudes, and approaches [that allow] different people and different cultures [to deal] with one another in a mutually constructive way.” Dambach, who was nominated for a Nobel Peace Prize for his mediation efforts in Ethiopia and Eritrea, was profiled in the Winter 2022 issue of this magazine.

While it’s hard to state definitively that the work of Peace Corps Volunteers has helped the countries where they serve to prevent, mediate, or rebuild from conflict, it’s equally difficult to make the case that it hasn’t.

“Peace Corps may not track peacebuilding per se, but it is clearly a product of its work. For example, there are 12 presidents of African countries who credit a Peace Corps Volunteer with starting them on their path to presidency,” says Kim Dixon, who heads up Partnering for Peace, an NPCA affiliate group that brings members of the Peace Corps community together with Rotary International to pursue the goals of international peace, friendship, and service. The group has been instrumental in helping Volunteers find ways to support Ukrainian refugees, and work together to award fellowships to young people dedicated to fostering peace. Many Returned Peace Corps Volunteers also go on to play important roles in peacebuilding after completing their service, either in the diplomatic corps, development agencies, or international institutions. “A lot of our colleagues in USAID are Peace Corps [alums], and it’s an absolutely fabulous experience if you want to come back and do development work,” says Jenkins, of USAID.

Susan Greisen (Liberia 1971–73) of the Friends of Liberia affiliate group has no doubt that Peace Corps Volunteers have had an impact on peacebuilding efforts in her former host country. Though Peace Corps was not present during Liberia’s brutal civil war, which lasted from 1989 to 1997, many RPCVs remained engaged with people and programs in the country, offering support from abroad that continues today.

“My village was destroyed. The people were destroyed. So in some ways I look back on my experience and think that all the good that I did is gone,” Greisen says. Nevertheless, she says, “One of the very first Volunteers who returned to Liberia after the war said to me, ‘Susan, when we came back 20 years later, they said, We remember the schools you built, the roads you constructed, the clinics you supported. We remember Peace Corps.’”

Like most RPCVs dedicated to fostering peace, Chic Dambach remains hopeful, reminding us that while the current state of the world may look dismal in terms of conflict, many countries are doing well, accordng to the Global Peace Index. “If you want to become an Olympic gold medalist, you wouldn’t study the people that never made the team. You study the people that won the gold medals: What are they doing right?” he continues. “At the end of the day, peace is simply something that has to be built.”

Robert Nolan (Zimbabwe 1997–99) is editor of WorldView.

You can reach him at [email protected]

Illustration by Doug Chakya