The creation of maps has long been a favored secondary project or PCVs. Do they help communities see the world in a different way?

by David Arnold

Women prepare the base for a world map in Barsalogho, Burkina Faso, in 2009.

Forestry Volunteer Barbara Jo White (Dominican Republic 1987–89) wanted to plant fruit trees near the school in Hondo Valle, the small town she lived in on the Dominican Republic’s mountain border with Haiti. “What happened was some fruit trees came my way, and I made compost and all of that stuff and planted my fruit trees on the border of the school grounds,” White says. But after the fruit trees were planted, the school’s head- master decided to lease the plot to a farmer, who tilled it with oxen to sow his bean crop.

When Peace Corps’ forestry sector director drove to town to examine the progress of White’s fruit trees, White was devastated to see her nursery had been plowed into the ground. “I just cried that day,” she recalls, “but it gave me free time to work on other projects.” The idea of painting a large map on a classroom wall took seed when a nearby Volunteer told White she was going to ask the National Geographic Society to send a world map for her classroom. “The only way to get a map to stay on the wall is to paint it there,” White replied. So she bought a global map in the country’s capital city of Santo Domingo, drew a grid on it, and worked with two young Dominicans to copy the map onto the wall of a classroom at the Hondo Valle school, first drawing the lines by hand, then filling in the countries and oceans with different colors of paint. It was the first time there had ever been a world map inside a classroom at the school.

A year later, in 1988, White used a $20 donation from another Volunteer’s brother to organize a mapmaking workshop for about 20 of her counterparts and a few other Peace Corps Volunteers. Together they painted another large map—6 feet tall by 12 feet wide—on the outside of the school. The sunny side of the building was so hot that day that some of the mapmakers had to hold umbrellas so others could draw and paint in the shade. Everyone was so intent on their work that they wouldn’t even stop for a free lunch. “Oh my gosh,” White thought, “we’re onto something.”

Inspired by the success of these two projects, White wrote a how-to manual and workshop planning guide to spread the word about mapmaking to other PCVs serving in her host country. With the help of a Peace Corps Partnership grant, other Peace Corps Volunteers held 10 more mapmaking workshops in the Dominican Republic that year. And the World Map Project was born.

The Monster Map

In 1989, the World Map Project came to the States when Tim Carroll, the president of the National Council of Returned Peace Corps Volunteers (now National Peace Corps Association), heard about White’s mapmaking workshops in the Dominican Republic. I was so impressed with what she had done,” Carroll recalls. He sent staffer Laura Byergo to Hondo Valle to work with White on planning an 18-foot-by-36-foot so-called “Grand Map, which would be hung on the side of the 12-story Hilton Hotel in Eugene, Oregon, during the council’s 11th annual conference in July 1990. White partnered with Bonny Tibbitts, a member of the local West Cascade RPCVs, to organize and assemble a map like no other. The hundreds of RPCVs who attended the 1990 conference were invited to paint the map and then help hoist it onto an exterior wall of the hotel. Described at the time as “the world’s largest hand-drawn map” and given the nickname “the monster map,” the Grand Map inspired the creation of other large maps, including one that was displayed at a later post-genocide Rwanda and Ethiopia and conference in Atlanta, Georgia, and one at the 1996 Summer Olympics.

Revelers admire the so-called “Monster Map” created at a 1990 RPCV conference in Eugene, Oregon.

Other groups, like the one in Greater Birmingham, have drawn and painted maps in Alabama schools. In the process of making large public maps like these, students in the United States and other countries have learned about their distinctive place in the world. They have discovered the greater significance of the shapes created by shores, rivers, mountain ranges, and national boundaries, and they have learned how quickly those boundaries can change. In 1991, for instance, one of the returned Volunteers who had helped paint the monster map in Eugene was teaching at an international school in Nairobi. She gathered students from her eighth-grade social studies class and a math class to mount a world map painted on 14 wood panels on the blank wall of their school’s multipurpose building. The challenge was that, thanks to the recent collapse of the Soviet Union, they had to adapt the map to include newly independent countries like Ukraine and Lithuania

Part of a Culture of Peace

National Peace Corps Association continued to support the World Map Project through its global education program, but in 1994, NPCA president Chic Dambach created the Emergency Response Network to directly involve former Volunteers in solving conflicts along the borders depicted on some of those maps—including post-genocide Rwanda and Ethiopia and Eritrea, which were engaged in a lengthy border war from 1998 to 2000 (see “Where Is the Peace?” on p. 22).

While making maps is a peaceful com- munity-building enterprise, Dambach says it’s only a start. “The map is part of a larger initiative … that is, building a culture of peace.”

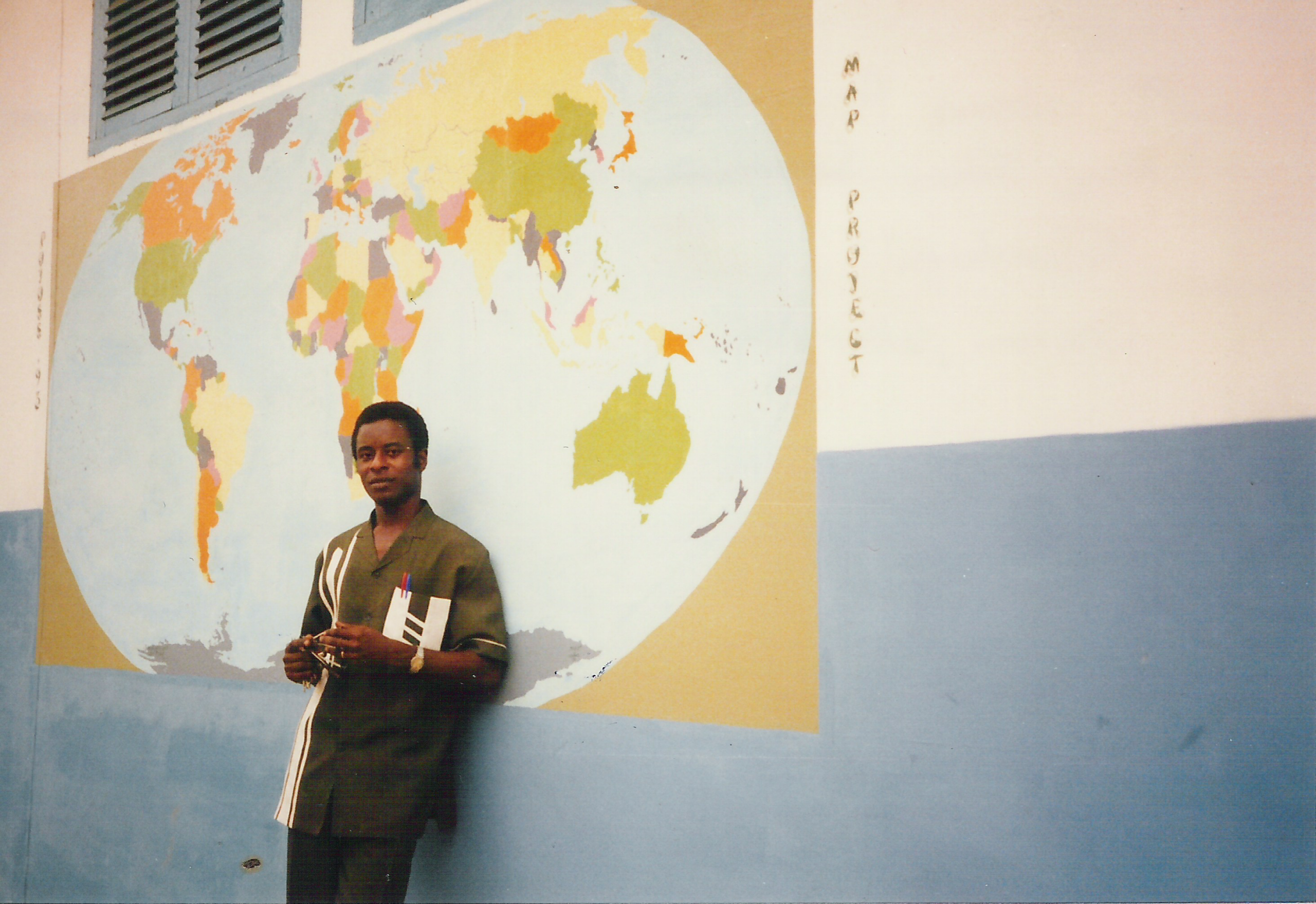

Pope John Koforidua stands in front of a world map created in Ghana during the early 1990s.

The first map White painted in the Dominican Republic was based on the so-called Mercator projection, which was originally designed to accurately depict compass bearings for sea travel and to ensure precision in representing local shapes at infinitesimal scales. Since then, Peace Corps map projects have undergone their own occasional cartographic twists. At Peace Corps’ 30th anniversary conference in Washington, D.C., White built an edible version of the world map out of Rice Krispies and marshmallows. In another variation, Han- nah Engel-Rebitzer (Costa Rica 2010–12) identified 20 emerging artists in Africa and Latin America and now markets their maps—a collection of abstract and personal perspectives on country and culture—at the World Maps Collaborative online. The mapmaking artists include Izabiriza Moise, who depicts Rwanda’s 30 districts using pieces of fabric and acrylic on canvas; Nasser Mejia Moreno, who maps places and cultural symbols on a map of Nicaragua; architect Micaela Cloete of Port Elizabeth, who depicts the boundaries of South Africa in fabrics; and self-taught artist Thobias Minizi of Tanzania, who creates images of his country out of fabric and paint.

The Power of Maps

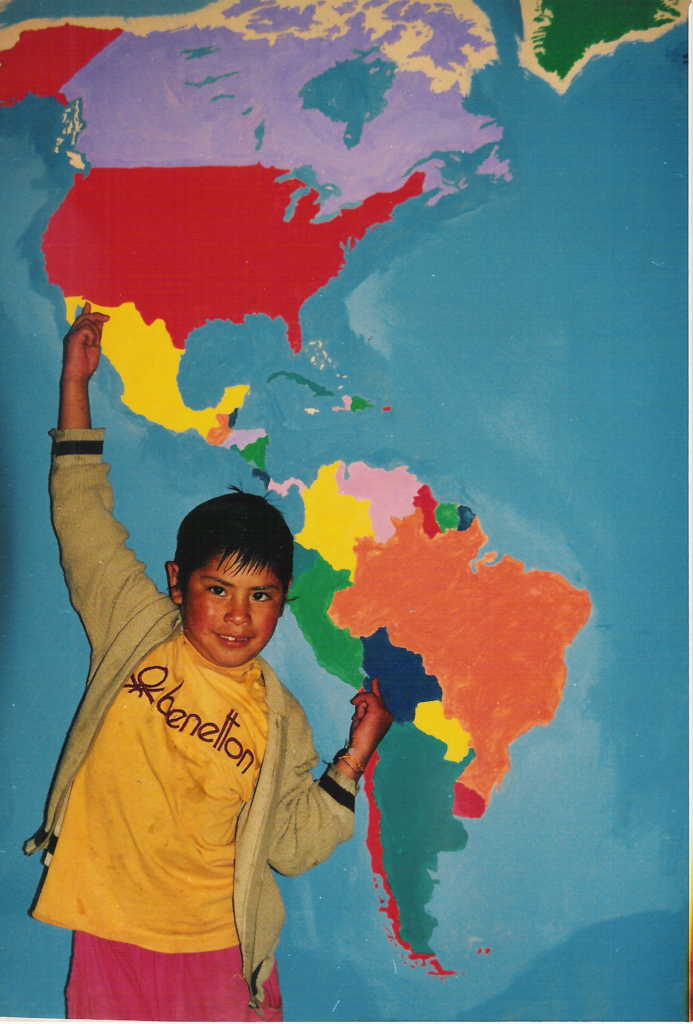

A student in Bolivia points out the connection

between his country and the United States.

Now a professor of computer information systems at Western Carolina University, White still tracks new mapmaking projects around the

world through letters and email. Emergency Response Network volunteer Alyssa Dimond (Sierra Leone 2013–14, Comoros 2014–15) discovered a weathered world map on the outside of the public lycée in Fomboni, Comoros. The date on the map was 1994, but the name of the Volunteer who had signed it was illegible. Dimond then organized her own mapmaking project in the town center in Mbéni, Comoros. Students of Jasmine Liu (China 2013–15) in Leshan, a city in China’s Sichuan province, were moving to a new building soon, so they put their map on a banner they could take with them. George Durgerian’s (Thailand 1989–91) TOESL students had to make a second map when the cement underneath their first one cracked and crumbled. Joseph Nsiah of Ghana wrote that after he worked on a world map, many neighbors in his district called him “Boy Wonder”: “It seems they have not seen art students like me in that district working on [creating maps] like I did.”

The World Map Project is still popular in the United States and overseas. Peace Corps has worked with White and others to pro- duce several versions of the World Map Project manual, with White hand-tracing and updating pages of the grid several times over the last 35 years. The agency has adapted White’s practices to create step-by-step World Map Project toolkit, available on the Peace Corps website. Serving Volunteers are still creating World Map Project maps in communities around the world. Peace Corps reports at least 15 maps currently in progress, with some recent maps taking a new approach to the changing times, focusing on local geography and even incorporating infographics.

“Humans create all maps with their own biases, even unintentionally,” says Nicole Bennett (Vanuatu 2015-17), who is currently pursuing a doctorate in geography at Indiana University. Bennett built innovative maps during her service that deviated from the traditional Eurocentric maps used by most of the world for decades. “I realized that the kids didn’t have access to a lot of visual information about Malekula (our island), Vanuatu, or the globe. Painting the island map was the most fun, because as we started marking the names of different places, the kids would talk about their travels to see families in different villages. Having the local and contextual maps helps to bridge villages and build community,” Bennett says. After all, she adds, “Knowledge is power.”