A conversation with Emmy Award-winning producer and RPCV Baktash Ahadi

by Robert Nolan

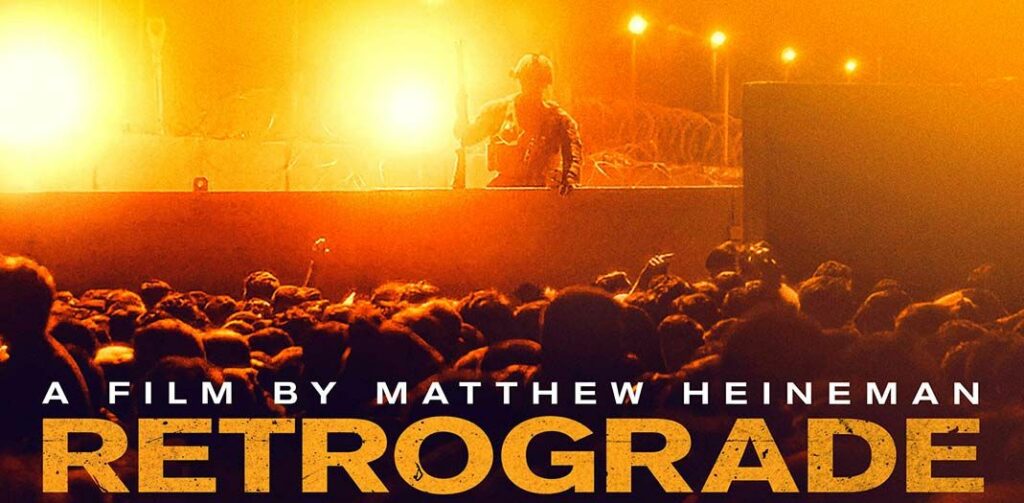

Baktash Ahadi (Mozambique, 2005– 07) is an award-winning filmmaker, human rights activist, TEDx Speaker and RPCV. His latest film, the Emmy Award winner Retrograde, offers a first-hand account of the controversial U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan and the human toll the war has taken on Afghans and Americans alike. Below is a condensed and edited conversation Ahadi had with WorldView editor Robert Nolan.

Robert Nolan: When I watched the film there was a particular scene when the Green Berets are breaking the news to their Afghan counterparts about the U.S. withdrawal. You could just feel how emotional those guys were and how much respect they have been had for their Afghan counterparts. Like you, they were certainly invested in that country. How heartbreaking was it to see it all fall apart?

Baktash Ahadi: That scene, I think, depicts a microcosm of the Afghanistan-United States relationship. What’s interesting about the 20-year war that the United States waged in Afghan- istan is that countless American veterans went to serve and many made countless sacrifices—in some cases, the ultimate sacrifice of dying for a war that, after 9/11, many of them believed in. What that scene depicts is how much everybody cared for the well-be- ing of one another, Afghans and Americans alike. I think the Green Berets in that scene were deeply disappointed because they were the ones delivering this horrific news, knowing that these Afghans would feel like they’re being abandoned.

And I think that’s ultimately what many people feel now, those that gave so much to Afghanistan. We have to understand that Afghanistan was an entire state-building project. So many Volunteers that we know, Returned Peace Corps Volunteers, ended up joining USAID, international development firms, media outlets, and other organizations working in Afghanistan. So it was an entire effort from A to Z to try to build Afghanistan up. And so many people fell in love with the process and the people along the way.

Nolan: So did anything good come out of this?

Ahadi: I think most people feel, especially in the U.S. military community, that their service was in vain. Something like 6,000 U.S. soldiers and American contractors died in Afghanistan throughout the course of the war. And something like 70,000 Afghan soldiers died during that time frame. What’s astonishing is that six times the number of U.S. veterans have died in America due to suicide: 36,000 American veterans. My next film project is actually about how combat veterans can find mental and relief through equine therapy.

Nolan: I expect it must very difficult for you to experience the emotion and tragedy of this war and then receive so many accolades for the film. Lots of Americans were checked out on Afghanistan for so long, so to have people come up to you and say, “Wow, this is a really great film! Here are some Emmy Awards.” How did you handle that?

Ahadi: In terms of being a film-maker, what’s really interesting about Retrograde, and I think why it’s likely going to continue to be an important document and artifact as a matter of under- standing what war looks like, is that it’s the first film ever made that actually captures the end of a war. When we think about World War II, Korea, Vietnam, Desert Storm, or Iraq, none of those wars were captured in a film the way Retrograde captured the end of the war in Afghanistan. We have images of the U.S. leaving Saigon, and we may even have videos, but we don’t have an actual film. I want to say that because that’s what gave me inspiration to say, “This is why it matters.” It’s going to outlive me. People that study war, people that study foreign policy, people that have studied security will come back to this film and say, “Let’s see what it is that an end of a war looks like and how much can happen.” That was so unexpected.

[Director] Matthew [Heineman] intended to make a film about the life cycle of the last Green Beret unit in Afghanistan, from leaving their homes in Colorado to going to Helmand [Province] and then coming back to their families. That’s what the film was going to be. So when President Biden announced the American withdrawal in May of 2021, all of a sudden the film changed into something completely unexpected.

That’s what gave me the inspiration to get through all this. You notice in the scene of the withdrawal at the airport that there’s no real dialogue. There are no interviews. Its purpose is to say, “This is what it felt like.” And that’s what gave me the inspiration to say, “I want people to know what this moment was like.”

It stays with people. As a filmmaker, that’s the most important thing. We want to elicit emotion from the viewer. So the accolades that came afterward, I think, were given because it made people feel like they were actually there.

Nolan: All people can relate to heartbreak.

Ahadi: I think Peace Corps Volunteers will really appreciate that there’s something about some cultures that just stay with us. The single most important thing that I think most Volunteers feel when they step into a community is a sense of hospitality. It is one of my favorite qualities of a culture—to ask, how hospitable are these people?

And hospitality for me is an invitation to be seen in somebody else’s world. If you ask those that have served in Afghanistan or have been to Afghanistan, they love it. They will tell you, “The Afghan people were very hospitable to me. They welcomed me in ways I couldn’t possibly begin to imagine. They would go out of their way to make sure that I felt safe as a guest in their home.” And that’s what U.S. service members felt in Afghanistan. That’s why they gave so much.

To that end I would say that Americans have a very, very important question to ask: What is the responsibility that we have when we go into

Baktash Ahadi (Mozambique, 2005–07)accepts three Emmy Awards for

the film Retrograde in 2022

other countries, either by invitation or by force? In the context of Afghanistan, we were invited to take on the Taliban there. I’m not sure if you remember, but there were celebrations when the United States went into Afghanistan after 9/11. Men were cutting their beards off. There were photos of people celebrating in the streets. So the United States was invited to come, and [it] stayed for a very long time. We promised to, and did, give a sense of hope to the Afghan people. And there’s a difficult thing that came out of that, something called moral injury—the idea that a person’s world is flipped upside down in terms of what they believe to be true in the world. It’s in the realm of PTSD, but it’s actually a soul wound. That’s what’s happened to a lot of Afghans. It’s really hard to come back from.

Nolan: In the film, one of the Green Berets defines the term “retrograde” disparagingly as “shitting in a trench.” Could you help define the film’s title and why you chose it?

Ahadi: “Retrograde” refers to the idea of going back. And that’s exactly what happened. It captures this idea of trying to oust an insurgent regime known as the Taliban, and [now], after 20 years, they’re back in power. And when you think about all we’ve given, the question that always surfaces is: Was it worth it? What do we do here? Was it better to not go at all? Or was there some- thing here that we gave these people—say, a semblance of hope—and then we took it away? So Retrograde, the title, comes from this idea of going back to where we started. That’s the tragedy of it all.

Nolan: Did your Peace Corps experience help prepare you for all this in any way?

Ahadi: It’s actually a question that many Peace Corps Volunteers have a hard time answering upon finishing their service. What did I do and how do I kind of position myself in a way that’s going to be marketable? That’s something that plagues many Returned Peace Corps Volunteers. And what I would say is that, upon reflecting on my experience 15 years ago, the power of the Peace Corps is the power of experiences. You go into a country thinking that you are going to offer some semblance of light to this community that you were assigned to. And over the course of two years, these people have changed you in ways that you couldn’t possibly have imagined. That’s the magic of the Peace Corps experience. That happens because you’re put in positions and situations with people that have a perspective completely different than yours. What you’re required to do is to actually engage and to talk to them and learn about them.

Why do I share this? It’s because this sense of engagement and this sense of curiosity is actually, I think, the foundation for filmmaking and storytelling. As Returned Peace Corps Volunteers, we come back and tell stories of our experiences. And this sense of what I like to call “radical curiosity” about a place in the world is the key to filmmaking. That’s something I learned specifically in the Peace Corps.

Baktash is currently at work directing a documentary film about combat veterans, mental health, and equine therapy. He also supports other filmmakers from concept to impact campaign as an executive producer and impact producer. You can follow him on LinkedIn and Instagram.

Basktash invites you to reach out if you’d like to collaborate on any filmmaking projects. His website is: https://www.baktashahadi.

WATCH THE TRAILER FOR RETROGRADE: