The historic Journals of Peace event in the U.S. Capitol Rotunda saw little security—and lots of stories

by Tina Martin

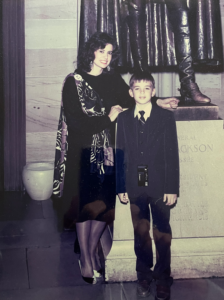

Tina Martin (Tonga 1969–71) with her son Jonathan in Washington, D.C. for the Journals of Peace event in 1988

January 6th is a date most Americans will not soon forget. Looking back now, after the insurrection, I marvel that, in 1988, 400 of us Returned Peace Corps Volunteers were invited to spend 24 hours in the Capitol Rotunda with little more than the directive that we provide our names and Social Security numbers—and this was after closing hours!

The event, dubbed “Journals of Peace: A Very Special Commemoration by the National Council of Returned Peace Corps Volunteers,” was first announced in the Fall 1988 issue of this magazine, WorldView. The announcement read: “Come join us for this singular event. A 24-hour vigil Nov. 21–22 commemorating the founder of Peace Corps, John F. Kennedy, in this 25th year since his death. Hundreds of Returned Peace Corps Volunteers will read from their Peace Corps journals—passages explaining what we learned in Peace Corps and what Peace Corps meant to us individually. That’s why we call it Journals of Peace. Make a reservation with us now to share your personal words with the world.” The event would take place from noon to noon, beginning on the 21st, and Volunteers were asked to prepare 500 words—roughly three spoken minutes—from our Peace Corps diaries, our letters home, or the “best recollection that crystallized for you the Peace Corps experience.” The 24-hour Journals of Peace vigil would be followed by a commemorative service at St. Matthew’s Cathedral led by the Rev. Theodore Hesburgh and Bill Moyers.

Somewhere down in my basement there were 28 notebooks filled with my Peace Corps diary, kept during my service in Tonga (1969–71), so I disinterred them and sent an excerpt through the U.S. Postal Service, as one did in those days before email. “I feel sure that you’ll get a lot of submissions that emphasize the volunteers’ virtues, sacrifices, and altruism, and I feel a little bit embarrassed that my submissions emphasize, instead, a volunteer’s gain,” I wrote in with my submission. “Most of my diary entries, from what I’ve re-read, tend to be humorous rather than profound, but President Kennedy had a sense of humor, and the people listening may need some comic relief after they’ve listened to accounts of philosophy, sacrifice, and struggle.”

March 1970: I’m living on $23 a month, which seems excessive in a tiny hut made of bamboo reeds and coconut leaves and lined with dozens of mats and pieces of tapa cloth, occupied wall to wall with children. When I sit on the floor with my back against the back door, my feet can almost touch the front door. There’s no electricity or running water, so I use a kerosene lamp and draw water from the well. There are breadfruit and avocado trees around my hut, and if I want a coconut, the children around my hut can climb a tree for me. At first, I had a little garden and six chickens. But I also had (and still have) pigs and goats, ducks and chickens and horses roaming around my yard, so my garden has been devoured. The chickens disappeared too, one by one, the night before each Tongan feast. But I came here to make a contribution, so if they’d rather have my chickens than my eggs, at least we know now which comes first—the chickens, not the eggs. The kids I teach are always with me, and I love them more than I once loved my privacy. I always wanted to have children someday, but I never thought I’d have so many and so soon… After school the children come home with me and stay, singing Tongan songs and ones I’ve taught them. They know lots of Broadway show tunes now, but the song that has really stuck is, unfortunately, [the theme song for] “The Mickey Mouse Club,” which one day in a fit of cultural imperialism I taught them. It may be the closest they ever get to Disneyland… The children never leave until I am safely tucked into bed under my canopy of mosquito net and on top of tapa cloth. I write in the exercise book I use for my diary and keep with me every moment of the day. Then I blow out my lamp and think about how much I love this village. And I think about Vietnam, where villages like this are being targeted. And they never report killing children. They never report killing Vietnamese. They only report killing communists. I’m in total darkness once I’ve blown out my lamp. There’s no electricity in this village, so there’s no light at all—unless there’s a full moon. And the full moon is fully American, a Tongan teacher told me last week. It’s been American ever since last year when the astronauts landed and planted the American flag, claiming it for America, he said. I smiled and told him, “But the sun is Tonga’s.”

I enclosed a self-addressed stamped envelope “for you to return my submissions to me if you can’t use them.” But a November 1988 diary entry reads, “I got a letter saying they were reserving a three minute slot for me.”

I didn’t think I could afford to fly from San Francisco to Washington, D.C., for Journals of Peace, but I made the financial sacrifice—losing wages and coming up with plane fare. Karen Keefer, an RPCV and a FEMA worker, welcomed me and my nine year old son, Jonathan, into her home so we could afford to be there for what turned out to be the most memorable Peace Corps event I’ve ever attended.

Before reading from our journals, some of us addressed President Kennedy as if he could hear us. The next morning USA Today ran my picture and a quote:

“Dear President Kennedy, I look longingly to the year—more than a quarter of a century ago—when you appealed to our better instincts and elicited idealism instead of cynicism and opportunism. When you uttered the much quoted phrase ‘Ask not what your country can do for you; ask what you can do for your country,’ you were wise enough to provide us with some answers. One … was the Peace Corps, which I think has benefitted our country as much as its host countries by giving us a larger perspective and teaching us to think globally.”

A copy of the USA Today article covering Journals of Peace

Also pictured in USA Today was Sally Timmel of Washington, D.C., who had served in Ethiopia and whose diary entry, dated November 22, 1963, was quoted: “Ron Kraus came through the door saying, ‘President Kennedy is dead.’ Our shouts of denial did nothing to make the moment seem any more real. I laid awake feeling sick, listened to the hyenas hollering … and the crying of sick children. The sounds of the world seemed to continue, but I felt that I not only had lost a rudder that gave us direction but lost a part of (myself).”

Following the readings, seamlessly, peacefully, we 400 RPCVs moved from the Capitol building to St. Matthew’s Cathedral for a service attended by 1,500 people including guest speakers Sargent Shriver, Director of the Peace Corps at its inception, and Moyers. We carried flags representing the countries in which we’d served.

On the 35th anniversary of Journals of Peace last fall, I got out my 1988 diary and photo album documenting the event. I have a letter from Tim Carroll, the first director of the National Council of Returned Peace Corps Volunteers (now National Peace Corps Association), from December 1988 acknowledging the interest others had shown in getting a recording of the 24-hour reading or a compilation in writing of what was read there.

Alas, there was no internet or easy file-sharing mechanism in those days, and even though there was an effort to put the readings online in 2017, Journals of Peace now seems lost to history. I’m grateful that Peace Corps has used excerpts from my submission “Under the Tongan Sun” for recruitment since the late 1980s, but I’d like the other journal excerpts to be resurrected.

In his 1988 letter Carroll writes, “The season when peace is briefly popular is coming upon us. I suppose we should be pleased that it gets center-stage once a year. We certainly put it in the spotlight on November 22.”

My Christmas present to my son Jonathan, 35 years after the Journals of Peace reading, is an album featuring a photo of him posing with me in Washington, D.C., in the Capitol Rotunda.

Tina Martin (Tonga 1969–71) taught English as a Second Language in Tonga, Spain, Algeria, and at City College of San Francisco for 32 years.