Volunteers show resilience and feel heartbreak amid the agency’s global evacuation

Volunteers show resilience and feel heartbreak amid the agency’s global evacuation

By Tasha Prados

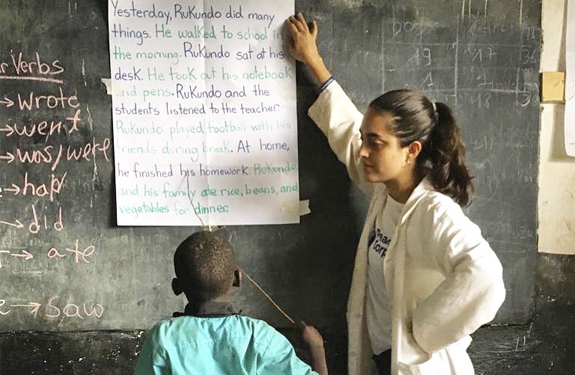

Photo courtesy Ana Santos

“Hours before our flight, at our Close of Service conference, my [Peace Corps] Country Director asked me how I was feeling,” Quinton Eklund Overholser said. “Only then did I muster a single word: heartbroken.”

Overholser had been dreaming of serving as a Peace Corps Volunteer in Myanmar since his first year of high school — even before the Peace Corps operated in Myanmar. He was in Myanmar training to become a Volunteer when, in mid-March, the Peace Corps suspended operations for the first time in its history and began an unprecedented evacuation of all of its more than 7,300 Volunteers from around the world.

The evacuation effort was herculean and frequently chaotic. But the circumstances were unprecedented, too, as the coronavirus pandemic spread around the globe.

Typically, Volunteers receive 12 weeks of in-country training, complete two years of service in their respective sites, and go through a Close of Service (COS) process involving extensive medical checks and a conference to prepare them for reentry into American society and finding jobs post-service.

But these are not ordinary times.

Evacuation and community

Evacuations followed different processes from country to country — since circumstances on the ground were different, too. Of those evacuated Volunteers I spoke to for this story, some received different information regarding what they should do when they returned home regarding self-quarantining, what would be reimbursed, as well as their benefits and pay. Some were initially told they were on administrative leave, but ultimately, all were COS’d — meaning their service was closed out — which unlocked some benefits that otherwise would not have been available to Volunteers on hold. It’s also difficult to forecast at this point if and when Volunteers might be able to return to service.

Volunteers I spoke with also said they were told they were not eligible for unemployment because they were not technically “employees.”

Normally Volunteers receive one free month of health insurance when they return. That was extended by Peace Corps to two months. But the evacuated Volunteers haven’t gotten allotted COS medical checkups; and nationally, non-critical medical appointments have gone on hiatus. (Here, too, legislation has been introduced.)

The Peace Corps has scrambled to develop this and other policies for these new circumstances, and has been regularly updating the agency website with new information.

Far sooner than they had planned, many of the evacuated Volunteers have turned to National Peace Corps Association for advice and assistance. A nonprofit advocacy organization, NPCA works on behalf of more than 240,000 Returned Peace Corps Volunteers — and lobbies on behalf of the agency. NPCA is headed by Glenn Blumhorst, who served as a Volunteer in Guatemala 1988–91; he connected by chat with the Volunteers in Guatemala as they were being evacuated just a few weeks ago.

NPCA had been developing a new program called Global Reentry to assist returning Volunteers; the timeline on it was quickly stepped up, and the program rolled out in March. The program is meant to connect evacuated Volunteers with the broader Peace Corps community; provide a clearinghouse for information on academic resources, counseling, and job searches; assist Volunteers trying to continue projects back in the countries they served; and provide financial help for those in dire need.

Volunteers who sign up for Global Reentry are also kept up-to-date on NPCA’s advocacy efforts: to address that question of unemployment compensation; extend health benefits; expedite hiring of RPCVs using their Non-Competitive Eligibility for federal job openings; and redeploy quickly when it’s safe for Volunteers to return to the field. By the end of the first week of April, those advocacy efforts bore fruit with new legislation introduced in the Senate to extend health benefits for volunteers for six months. The following week bipartisan-sponsored legislation was introduced in the Senate that would make evacuated Volunteers eligible for unemployment coverage.

Grassroots help

Many of the evacuated Volunteers have also turned to informal networks for information and support. One such group on Facebook, Returned Peace Corps COVID-19 Evacuation Support [Community-Generated], was launched on March 16. It had 200 members within the first hour and 2,000 within the first day. The group now has almost 9,000 members and has facilitated the transfer of over $25,000 to help evacuated Volunteers. Returned Volunteers and parents of RPCVs have given airport rides and ferried groceries, offered job help and resume reviews and tips for graduate school. They’ve also provided critical emotional support to evacuated Volunteers — who already have their own community-generated acronym: ERPCVs, for Evacuated Returned Peace Corps Volunteers.

Joshua Johnson, a returned Peace Corps Volunteer who started the group, realized he didn’t need to wait for someone else to take action — he could help the ERPCVs by bringing the community together and centralizing resources. “Leaving Peace Corps after months of preparation was difficult enough,” said Johnson, who served in The Gambia from 2009 to 2011. “I can only imagine what it is like to be so quickly pulled out of site.”

Grassroots help: Joshua Johnson and family. Photo courtesy Joshua Johnson.

This is a volunteer effort by Johnson, who didn’t expect the group to take off the way it did. He says he’s been blown away by the kindness he has witnessed. “In reality, responding to an emergency situation by coming together as a community gets to the heart of the Peace Corps values and really is what we have trained for,” he said. “In the face of an uncertain situation, and with limited resources, we are able to use our creativity and resourcefulness to come together to make sure that everyone is taken care of.”

A dream deferred

For Quinton Overholser, the evacuation from Myanmar put in harsh relief the joy he had felt just a few months before. A first-generation college student from Elko, Nevada, he got his Peace Corps acceptance on the day of his commencement ceremony at the University of Nevada at Reno: “My eyes filled with tears of joy. My dream was becoming reality.”

Head of 100 Households: Quinton Overholser with his host family. Photo courtesy Quinton Overholser.

Overholser loved every day in Myanmar, he said, learning to read, write, and speak Myanm, and spending as much time as he could with the local family who hosted him. He went to meetings with his local father, the “Head of 100 Households” (Mayor). He learned about Myanma music from his sister and played games with his brother.

He says the hardest part of the evacuation was leaving the family he’d grown so close to. “I was left with such an empty feeling, having never moved to my permanent site or even taught one day in my own classroom.”

While he was happy to reunite with his American family, Overholser says returning home to his small town in Nevada under quarantine felt like more of a defeat than a return from service. But Overholser is still committed to his dream. He is waiting to return to Myanmar as a Peace Corps Volunteer. The question is if and when that will be possible.

Service, interrupted: Marissa Kelemen. Photo courtesy Marissa Kelemen.

Saying goodbye

For other evacuated Volunteers, completing their service may not be an option — especially given immediate and practical needs in an uncertain economy. “I’d love to be able to hop on a flight right now and go back to Zambia,” says says Marissa Kelemen, who began her service there in September 2018. “But, realistically, who knows how long all of this could take? Waiting for the return to service clearance isn’t a privilege all of us have, so I’m now looking for a job and am trying to restart my life. I’ll go back to Zambia, but not as a Volunteer.”

Kelemen says she had finally established a rhythm at her site in Zambia. She had found the right project to work on with her community, had just submitted a grant for the project, and was waiting for approval when she heard about the evacuation order.

The site where Kelemen worked didn’t have great cell phone reception; she didn’t find out about the evacuation order for several hours until after it was given, when she was in an area with better service. “My phone got overflooded with texts from other Volunteers talking about the evacuation,” she said. “I learned I only had one day to pack up my entire house, leave my school, and say goodbye to my host family… My whole conception of normal life had been completely ripped out from under me.”

“Peace Corps is one of the best ideas the United States ever had.” Ana Santos and student. Photo courtesy Ana Santos.

Others saw the order coming. Ana Santos, who is from the Atlanta area, had been serving in Rwanda since September 2018. She was with several other Volunteers shortly after hearing about the first confirmed case of COVID-19 in the country. They concluded evacuation would be inevitable, and she started packing her bags that Sunday, before getting the official evacuation order on Monday.

The Peace Corps’ global evacuation “was a difficult and unprecedented decision,” Santos said. “But ultimately, I think it was the right choice given these extreme circumstances.”

She quickly began the emotionally taxing and logistically challenging process of saying goodbye to the community that had been her home for over a year. The government had banned large gatherings and closed schools to reduce the spread of COVID-19. As a result, Santos’ teaching counterparts had returned to their family homes in other districts, and she couldn’t find many of her students. “I had to go to each of my teachers’ homes individually to greet them and tell them the news. They were as shocked and as upset as I was.”

Then Santos began the long trek to the capital, Kigali, coordinating with other nearby Volunteers to hire a bus to get them there as quickly as possible. In Kigali, the Volunteers completed administrative tasks and got medications from their Peace Corps medical officer. They had just arranged for flights home, she said, when the Rwandan government announced that the airport would close in 48 hours. With airports and borders closing rapidly, Peace Corps quickly chartered flights back to the United States. Santos remembers her country director saying the Peace Corps was “moving mountains” to get the Volunteers home.

In the face of adversity

The evacuated Volunteers, many still in shock and some still in self-quarantine in early April when we spoke, are wondering about their futures — and the future of the Peace Corps.

Originally from Vermont, Kelemen didn’t have a plan when she was evacuated because she wasn’t scheduled to finish her service for another seven months. “I’m trying to find a job, healthcare, and a place to live,” she said.

Many evacuated Volunteers are focused on immediate needs like Kelemen. The network of Returned Peace Corps Volunteers has sprung into action to help. “The community of returned volunteers is so generous and kind and it has been amazing to witness,” Johnson said. “The values of the Peace Corps have never been more important, and it has brought me untold joy to see the community come together in the face of adversity.”

“The values of the Peace Corps have never been more important.” Photo courtesy Marissa Kelemen.

Each of the evacuated Volunteers I spoke to for this story underscored the fact that, while their service hadn’t been easy, they were glad they made the decision to join the Peace Corps.

“I joined the Peace Corps because I wanted to serve and do my part to make the world a better place,” said Ana Santos. “I was excited by the opportunity to experience a different country and immerse myself in a different culture. I wanted to work face-to-face with people who were change-makers in their community. I wanted a task that was challenging yet fulfilling.”

And she got it.

The evacuated Volunteers felt strongly that this pandemic could and should not be the end of the nearly 60-year-old institution established to foster global peace and friendship.

“Peace Corps is one of the best ideas the United States has ever had,” said Santos. “There is no other program that sends these service-minded people out into all corners of the world in order to do good.”

Even in this dark and uncertain time, seeing the skills that Peace Corps service has fostered and the values that service has instilled in Volunteers has highlighted the need for the agency.

“What has really given me the most hope is seeing how the evacuating Volunteers have responded to this,” said Johnson. “Yes, there have been many moments of grief or frustration shared, but I also see a lot of hope as Volunteers have found ingenious ways to continue their project work, and continue to connect with their communities.”

This story was updated on April 19.

Tasha Prados is the founder of Duraca Strategic, which helps purpose-driven organizations maximize their impact through branding, business, and marketing strategy consulting. She has 10 years of project management and communications experience with the world’s leading brands, agencies, and organizations. Prados is also a freelance writer, digital nomad, and returned Peace Corps Volunteer who served in Peru 2011–13. She is also featured on the NPCA’s inaugural “40 Under 40” list. Keep up with her on Instagram at @t.prad.

Tasha Prados is the founder of Duraca Strategic, which helps purpose-driven organizations maximize their impact through branding, business, and marketing strategy consulting. She has 10 years of project management and communications experience with the world’s leading brands, agencies, and organizations. Prados is also a freelance writer, digital nomad, and returned Peace Corps Volunteer who served in Peru 2011–13. She is also featured on the NPCA’s inaugural “40 Under 40” list. Keep up with her on Instagram at @t.prad.