A Life Unimagined: The Rewards of Mission-Driven Service in the Peace Corps and Beyond

A Life Unimagined: The Rewards of Mission-Driven Service in the Peace Corps and Beyond

By Aaron S. Williams

International Division, University of Wisconsin-Madison

Reviewed by Steven Boyd Saum

Aaron S. Williams grew up in a segregated neighborhood on Chicago’s South Side in the 1950s. When he began studying geography at Chicago Teachers College, it was because the subject would offer him good career opportunities in the public schools. But, as he notes early in the memoir A Life Unimagined, “studying the geography of distant places around the world…the seeds once planted by my father of distant travels began to take root.” That’s not to say his father encouraged him to join the Peace Corps; he didn’t. But his mother and his best friend both did.

“My choice to join the Peace Corps changed everything,” Williams writes. For his mother, too; she would visit him when he was a Volunteer in the Dominican Republic, and over his two decades as a foreign service officer with USAID in Honduras, Haiti, Barbados, and Costa Rica. It was only because of failing health in her older age that she didn’t visit her son and his family in South Africa, where Williams was stationed not long after the end of apartheid. The day after he arrived to begin leading the USAID mission, Williams met President Nelson Mandela.

Rewind for a moment: After serving as a Peace Corps Volunteer 1967–70, Williams took on responsibilities for the agency coordinating minority recruitment. He earned an MBA at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, then went to work in the corporate world, learning the ropes in the food industry. That set him on track for work in U.S. government-supported agribusiness development in Central America.

The capstone of his career in public service came in 2009, when Williams was appointed by President Barack Obama to serve as Director of the Peace Corps—the first African-American

man to hold the post. During Williams’ tenure, the Peace Corps marked its 50th anniversary, with celebrations around the world. The agency also secured a historic budget increase and reopened programs in Colombia, Sierra Leone, Indonesia, Nepal, and — in the wake of the Arab Spring — Tunisia. In terms of program successes, Williams points to new and expanded initiatives in Africa to address hunger, malaria, and HIV/AIDS — through the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), the President’s Malaria Initiative, Feed the Future Initiative, and Saving Mothers, Giving Life.

Aaron Williams with Senator Harris Wofford at his confirmation hearing in 2009.

Wofford was a friend and mentor to Williams, and he introduced Williams that day.

Photo Courtesy of Aaron S. Williams

In terms of challenges, the year 2011 brought intense scrutiny to the agency following an investigation by the ABC news program “20/20” examining how six women serving as Volunteers had been victims of sexual assault. The program also looked at the tragic murder of Volunteer Kate Puzey, after she reported that a teacher at her site in Benin was sexually abusing students. Puzey’s death occurred some months before Williams became director, but the serious questions her murder raised about safety, security, and confidentiality still needed to be addressed. Williams worked with Congress to institute reforms, such as heightened security, and training and support for victims, that led to the passage of the Kate Puzey Peace Corps Volunteer Protection Act, signed by President Obama in November 2011.

Before his Peace Corps leadership role, Williams served as vice president of international business development for RTI International. In 2012, after stepping down from the directing the Peace Corps, he returned to RTI as executive vice president the International Development Group and now serves as senior advisor emeritus with the organization.

In his public writing in recent years, Williams has called on U.S. foreign affairs agencies to rise to demonstrate leadership in pursuing policies and programs that will improve diversity in their ranks by investing in the diverse human capital of our nation, to reflect the true face of America. And, not surprising, he has been a strong advocate for public service here in the U.S. Indeed, the foreword for his memoir—contributed by Helene Gayle, who formerly led the Chicago Community Trust and now is president of Spelman College, makes the case for that: “I hope that the life and career of Aaron Williams, as portrayed in this book, will inspire future generations of underrepresented groups in our society, both men and women, who seek to make a difference by serving America and the world at large.”

Celebrating Fifty Years

AN EXCERPT FROM A LIFE UNIMAGINED BY AARON S. WILLIAMS

The American Airlines Boeing 727 began its descent from our flight that began in Miami, passing at a low altitude over the beauty of lush, emerald-green mountains, aquamarine-colored ocean, and long white beaches. Eventually the sprawling city of Santo Domingo appeared, separated by the Ozama River as it coursed its way into the Caribbean. This country held special memories for Rosa and me—it was my second home and where she was born. We gazed over the country’s natural beauty during another landing in the modern Airport of the Americas, a trip we’d made so many times since 1969. This arrival felt very different from my first at the old airport in December 1967 when I was a newly minted PCV.

This return to my beginnings in the Peace Corps highlighted for me the incredible journey that began as a college graduate’s surprising path to adventure. Here, I met my beautiful wife, seated beside me as we returned “home,” back to where my life was transformed. We were going to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the warm, friendly relationship created between this nation and the Peace Corps Volunteers who had served here throughout its rich history. That unique, historical bond, forged in the white heat of the Dominican revolution and the U.S. invasion in 1965, had brought about this seminal moment. During that time of strife and struggle, many of the PCVs of that era gained the respect of Dominican citizens by vigorously supporting the country’s revolutionaries and not following the Johnson administration’s official policy during a crucial period in Dominican history.

This return to my beginnings in the Peace Corps highlighted for me the incredible journey that began as a college graduate’s surprising path to adventure.

On this trip, Rosa and I would be participating in a series of events to celebrate, commemorate, and treasure the more than 500 participants who had worked side by side with the Dominican people in the spirit of friendship and peace. Current and former Volunteers and staff would reunite at a three-day conference and share in the success of 50 years of Peace Corps work in the Dominican Republic. This auspicious anniversary also presented us with the chance to engage with Peace Corps Volunteers and staff worldwide and observe the scope and impact of the organization’s 50-year global engagement. I experienced firsthand the warm reception that Peace Corps Volunteers continue to receive worldwide.

Our gracious hosts for these anniversary events were Raul Yzaguirre, U.S. ambassador to the Dominican Republic, and country director Art Flanagan. Yzaguirre is an icon in the Hispanic American community and a civil rights activist. He served as the president of the National Council of La Raza from 1974 to 2004 and transformed the organization from a regional advocacy group into a potent national voice for Hispanic communities.

Many returned PCVs made site visits to the towns and villages where they had lived and worked, often hosted by the current PCVs; such a site visit was nostalgic for the former Volunteer and also an exciting historical experience for the local citizens. Rosa and I were very happy to enjoy once again the company of so many friends who shared this collective experience, especially Dave and Anita Kaufmann, Bill and Paula Miller, and Dan and Alicia Mizroch. The men all served as PCVs in the late 1960s, so the celebration also represented a special homecoming between lifelong friends! Further, we had a joyful reunion with Judy Johnson-Thoms and Victoria Taylor, the PCVs with whom I had served in Monte Plata.

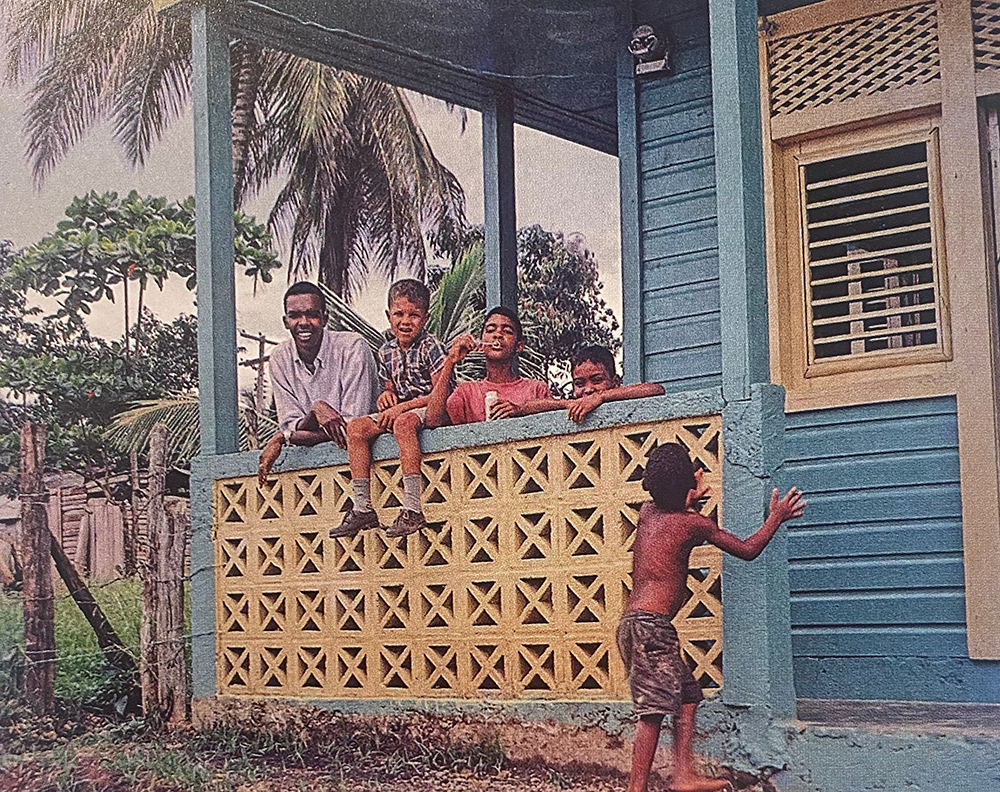

Monte Playa: As a Volunteer in the Dominican Republic, Aaron Williams, left, with his neighborhood buddies and informal language teachers.

Photo Courtesy of Aaron S. Williams

Dominican officials, our former counterparts, and many Dominican friends hosted events for Peace Corps participants in the grand style of a “family” reunion. Major Dominican newspapers and broadcast media provided extensive coverage of the celebration. Like many returned PCVs, I had the great pleasure of holding a mini-reunion with my former colleagues from the University Madre y Maestra, many of whom I had not seen since 1970!

We all felt honored to be joined by a special guest, Senator Chris Dodd, a proud returned PCV who served when I did in the Dominican Republic. During his five terms in the U.S. Senate, Chris had always been a great champion of the Peace Corps. For many years, he served as the chairman of the subcommittee responsible for oversight of the Peace Corps. Because he had presided over my confirmation hearing, it was especially gratifying to participate in this homecoming with him.

The planning for the Peace Corps’ 50th-anniversary celebrations, both in the United States and overseas, had begun before my appointment, under the previous director Ron Tschetter. Of course, we were enthusiastic about building upon these efforts. We were determined to hold a worldwide celebration that would highlight this significant landmark in the agency’s history and celebrate the legacy of this American success story — it would be a celebration to remember!

I have often reflected on the warm relationships between the Peace Corps and our host countries. The relationships that PCVs fostered for 50 years were indicative of the power of the organization in pursuing its mission of world peace and friendship. The outpouring of admiration, affection, and respect was something to behold as we continued preparing for these global celebrations. In each location, the country director and their staff created scheduled events representing the Peace Corps’ past and present role in each country, resulting in rich and diverse programs.

Those of us at headquarters planned several special events in Washington, D.C., to highlight and honor the Peace Corps legends who had been Sargent Shriver’s colleagues and to welcome the returned PCVs and other staff community back home. At the same time, returned PCV affinity groups — such as Friends of Kenya, Friends of Paraguay, and so forth—held anniversary activities in every state and in scores of colleges and universities across the United States. The national celebration aimed to demonstrate the organization’s continuing role in American life and history.

Overall, our senior staff traveled to 15 countries, 20 states, and 28 cities to celebrate the 50th anniversary. The Peace Corps senior staff worked to ensure broad representation; Carrie Hessler-Radelet, Stacy Rhodes, and I carefully planned our calendars to maximize our participation in major events in each region of the world and across the United States.

Our trips to visit the Volunteers in the host countries were a great privilege, and in my visits I stressed the importance of the individual and collective service of our PCVs and my personal connection with the work of the modern PCV. What a sight it was to see Volunteers on the front lines, working in microbusiness-support organizations to create new women-owned small businesses, teaching math and science in rural primary schools, or distributing mosquito nets in remote villages to fight malaria under our Stomp Out Malaria program, working in HIV/AIDS clinics, or helping small farmers improve irrigation systems.

The variety of PCV assignments was truly spectacular, from leading young girl empowerment clubs in rural Jordan, to coaching junior achievement classes in Nicaragua, teaching math in rural Tanzania, teaching internet technology in high schools in the Dominican Republic, teaching English as a second language in a girls’ school in rural Thailand, working on improved environmental protection practices in Filipino fishing villages, and helping to advise on improved livestock breeding techniques on farms in Ghana. Though I had once been in similar circumstances as a young PCV, I couldn’t help but be impressed by what I saw.

My colleagues and I had the pleasure of participating in several country celebrations during the 50th anniversary year, and it typically involved the following scenario. Of course, a meeting with the president of the host country and/or another senior government official would be first on the list for a country anniversary celebration. Many of these leaders had worked with or had been taught by Peace Corps Volunteers over decades. We also met with the leaders of the vital counterpart organizations, including community groups, government ministries, and the leading nongovernmental organizations in the country. We visited Volunteers at their worksites to observe their activities and attended a dinner or reception hosted by the U.S. ambassador for the PCVs, local dignitaries, and guests.

Another important aspect of my country visits was broad engagement with the national print, radio, and television press through press conferences, individual interviews, or both. In almost every case, returned PCVs who had served in a particular country participated in the events, often in coordination with the returned PCV affinity groups (e.g., in the case of Tanzania, Paraguay, Kenya, or Thailand), along with current PCVs and their guests. A typical visit for an anniversary event would run two days, and Carrie, Stacy, or I attended as the senior Peace Corps representative for a particular celebration.

Ghana is one of the most prominent nations in West Africa, and Sargent Shriver established the first Peace Corps program there in 1961. Its first president was the famous Kwame Nkrumah, who led the country to independence from Great Britain. Known during the colonial era as the Gold Coast, Ghana was also the location of some of the principal slave-trading forts in West Africa. Stacy Rhodes, Jeff West, and I traveled together to Ghana, where we spent three days in a series of events to celebrate the 50th anniversary in this historic Peace Corps country.

After our first day of courtesy meetings with government officials, local counterpart organizations, Volunteers, and staff, we decided to visit a famous fort. It was a heart-wrenching experience for Stacy and me, brothers in service, to stand before the fortress, built as a trading post with slaves as the primary commodity. We could only look out on the vast Atlantic Ocean through the “door of no return” in the bottom of that castle with sadness, knowing that those poor souls had been ripped from their native land. We felt it was necessary to witness the dungeons where they were held captive and the path they were forced to walk as they boarded the ships in the harbor that would take them to the West Indies or the American colonies, separating them forever from their homeland.

These are experiences not easily comprehended from afar, but they represent a crucial part of the human story that needs to be retold and remembered. Ideally, they set the stage for improving the human condition in the future.

One of the highlights of the trip was our participation in the country’s annual teacher day. I joined the vice president of Ghana, John Mahama, for this special event in an upcountry district capital. Stacy, the country director, Mike Koffman, and I were driven two hours from the capital city of Accra to the district capital. Mike had had a tremendous public service career, first as a Marine Corps officer, then as a founder of a nonprofit organization that provided legal services to the homeless in Boston, and then as an assistant district attorney in Massachusetts. After his stint as assistant district attorney, he served as a PCV in the Pacific region, and now we were fortunate to have him as our Ghana country director.

In Ghana, the top teachers were selected each year for special recognition. One of the ten teachers chosen that year was a PCV whose parents were both returned PCVs who had served in Latin America. This national ceremony honors outstanding teachers for their exemplary leadership and work that affected and transformed the lives of the students in their care and the community around them. The overall best teacher receives Ghana’s Most Outstanding Teacher Award and a three-bedroom house. The first runner-up receives a four-by-four pickup truck, and the second runner-up receives a sedan; indeed, a very different approach from how we honor teachers in America. I looked forward to participating in this important ceremony, during which the vice president and I would deliver speeches.

When we arrived at the government house in the district capital, I planned to discuss with the vice president a few points regarding the future of the Peace Corps program in Ghana. However, Vice President Mahama, who subsequently was elected president of Ghana in 2012, was more interested in talking about his experience with a PCV during his youth, and I listened to what he had to say with great interest.

He described how, as a young boy, he had attended a small primary school in rural northern Ghana. There were 50 to 60 boys in a very crowded classroom with very few desks and textbooks. They heard one day that a white American was coming to teach them, and they were anxious about this. They had never seen a white man before in their village, and they didn’t even know if they would be able to understand his language.

When the young American PCV came into the classroom, he looked around the class and said that he was going to teach them science. He then asked them, “Do any of you know how far the sun is from the earth?” The boys all stared at the floor; they didn’t understand why he asked this question or why it was important, but either way, they didn’t know the answer.

That day, for future Vice President Mahama, was a turning point in his life when he saw the possibilities of another world. He also told us about several of his friends from his village school in that same class who had gone on to become scientists or engineers.

The PCV walked up to the front of the classroom, took out a piece of chalk, and wrote down on the blackboard the number ninety-three; he put a comma behind it and then proceeded to write zeros on the front blackboard until he quickly ran out of room, and then he continued to put zeros on the walls of that small room, returning to the ninety-three on the blackboard. Then he exclaimed, in a loud voice, “It’s ninety-three million miles from the earth! Don’t ever forget that!” That day, for future Vice President Mahama, was a turning point in his life when he saw the possibilities of another world. He also told us about several of his friends from his village school in that same class who had gone on to become scientists or engineers.

From the government house, we went on to the stadium to participate in the teacher day festivities. Marching bands and students from all around the area welcomed us and an audience of thousands on the impressive parade grounds of the city. The vice president and I shook hands with and gave the awards to each of the winners, and we had a chance to meet the young PCV who had been selected as one of the winners. It was a long but satisfying day, and I’ll always remember my visit to this historic Peace Corps country.

I have equally vivid memories of traveling to a small village in Ghana, where we visited a young PCV from Kansas, Derek Burke. As I recall, he grew up on a farm, and now, in this remote and arid region of the country, he worked with the local farmers on a tree planting project, helping them to plant thousands of acacia trees. As we slowly walked into the village, we were welcomed by the hypnotic sounds of ceremonial drumming and greeted by more than 200 villagers. I loved seeing the smiling children as we met the village elders and local government officials. We then held a town hall meeting under an enormous baobab tree — a tree large enough to provide shade for all assembled.

As we departed, I was asked to visit with the patriarch of the village, who hadn’t been able to join us due to his failing health. He lived in a small hut on the outskirts of the village. The PCV and I went to his bedside. I can still feel the firm grip of the frail-looking gentleman, who appeared to be in his late 80s. He held my hand as he thanked me through a translator for visiting his village and for the “gift” of the young American PCV whom everyone loved. As I drove away, I thought about the symbolic importance of sending one Volunteer to serve in a remote village in Ghana and how he walked in the steps of those who came 50 years before him, in service to the country and the building of friendship in the name of the United States.

On a spectacularly beautiful day in June 2011, our plane landed in Dar es Salaam, the largest city in Tanzania, after a short stop in Arusha, near Mt. Kilimanjaro, where the majestic mountains loomed large from the airplane window. Esther Benjamin, Elisa Montoya, and Jeff West accompanied me. Dar es Salaam is a name that conjures up visions of Zanzibar and the ancient trading routes between Africa and the Arabian Peninsula. This nation, formed by the union of Tanganyika (colonial name) and the island of Zanzibar, has some fifty-five million citizens and is 60 percent Christian and over 30 percent Muslim, with two official languages: Swahili and English.

Tanzania was led into historic independence by the legendary Julius Nyerere, known as the “father of the nation,” who campaigned for Tanganyikan independence from the British Empire.4 Influenced by the Indian independence leader Mahatma Gandhi, Nyerere preached nonviolent protest to achieve this aim. His administration pursued decolonization and the “Africanization” of the civil service while promoting unity between indigenous Africans and Asian and European minorities.

The outstanding country program was led by one of our most experienced country directors, Andrea Wojna-Diagne, who received strong support from Alfonso Lenhardt, the U.S. ambassador to Tanzania.

In Tanzania, we started our visit by meeting with President Kikwete and his senior officials. It was a pleasure to learn that the president, as a young elementary school student, had been taught by a Peace Corps Volunteer. He had a very positive view of the Peace Corps, and he recognized its importance to the relationship between the United States and his country.

We started our visit by meeting with President Kikwete and his senior officials. It was a pleasure to learn that the president, as a young elementary school student, had been taught by a Peace Corps volunteer. He had a very positive view of the Peace Corps, and he recognized its importance to the relationship between the United States and his country.

We went upcountry to visit a volunteer who was a high school math teacher in a very remote part of Tanzania. In many places in the developing world, it’s challenging to find and hire science and math teachers for rural communities, who are desperately needed, as without these subjects, the students in this region would not be able to complete the coursework required to take the qualifying exams for university applications. The school principal and our PCV were very proud of the role he played in this school and of the astronomy program he created to introduce his students to this area of science.

Upon our return to Dar, we had the pleasure of attending a lovely dinner hosted by the ambassador and participating in a fiftieth-anniversary gala, organized by Peace Corps staff and the PCVs. Due to a touch of serendipity, there happened to be several Peace Corps volunteers in Tanzania who were graduates of performing arts programs in universities and colleges across the United States. They created, planned, rehearsed, and staged a magnificent performance about the history of the Peace Corps in Tanzania. The audience included current PCVs, returned volunteers, Tanzanian government officials, Peace Corps partners, and special guests. From my humble viewpoint, it was a Broadway-caliber stage performance. It included concert singing, highly skilled theatrical performances, original music scores by soloist performers, and poetry readings as odes to Tanzanian–U.S. friendship. There we were, on the beautiful lawn and garden grounds of the U.S. Embassy, being entertained by this incredibly talented group of volunteers who expressed their love for Tanzania in the most heartfelt, dramatic fashion possible.

In November of 2011, my team and I traveled to the Philippines to celebrate the joint fiftieth anniversary of USAID and the Peace Corps. My colleagues Elisa Montoya, Esther Benjamin, and Jeff West accompanied me on this trip. As in Thailand, Ghana, and Tanzania, the Peace Corps program in the Philippines was legendary, again launched by Sargent Shriver nearly fifty years earlier.

Benigno Aquino III was the son of prominent political leaders Benigno Aquino Jr. and Corazon Aquino, the former president of the Philippines.5 President Aquino was a strong supporter of the Peace Corps. In his youth, he had become friends with several PCVs in his hometown and had met many PCVs during his mother’s presidency.

Our ambassador, Harry Thomas, a distinguished veteran diplomat, had served as the head of the Foreign Service as director-general. USAID mission director Gloria Steele was also a veteran USAID officer and former colleague who had held several senior positions at headquarters. She had the honor of being the first Filipina American to serve in this position. Needless to say, Gloria was well known throughout the country and highly regarded across the Philippines. Our terrific country director, Denny Robertson, represented the Peace Corps.

The president graciously hosted a luncheon for our group in the historic Malacañang Palace, his official residence and principal workplace— the White House of the Philippines. Many meetings between Filipino and U.S. government officials have taken place there over the years of the countries’ bilateral relationship. We had a delightful, wide-ranging conversation with the president and his staff in which he made clear his great appreciation for PCVs’ years of service. He was pleased that we were there to celebrate the fiftieth-anniversary celebration of this highly respected American organization.

Excerpt adapted from A Life Unimagined: The Rewards of Mission-Driven Service in the Peace Corps and Beyond by Aaron S. Williams with Deb Childs. © 2021 University of Wisconsin-Madison International Division