Iran past, present, and future – with diplomat John Limbert, one of 52 Americans held hostage in Iran from 1979 to 1981. They were released 40 years ago this month.

Iran past, present, and future – with diplomat John Limbert, one of 52 Americans held hostage in Iran from 1979 to 1981. They were released 40 years ago this month.

From a conversation at the National Peace Corps Association 2020 Shriver Leadership Summit

Photo: The U.S. Embassy in Tehran, seal defaced

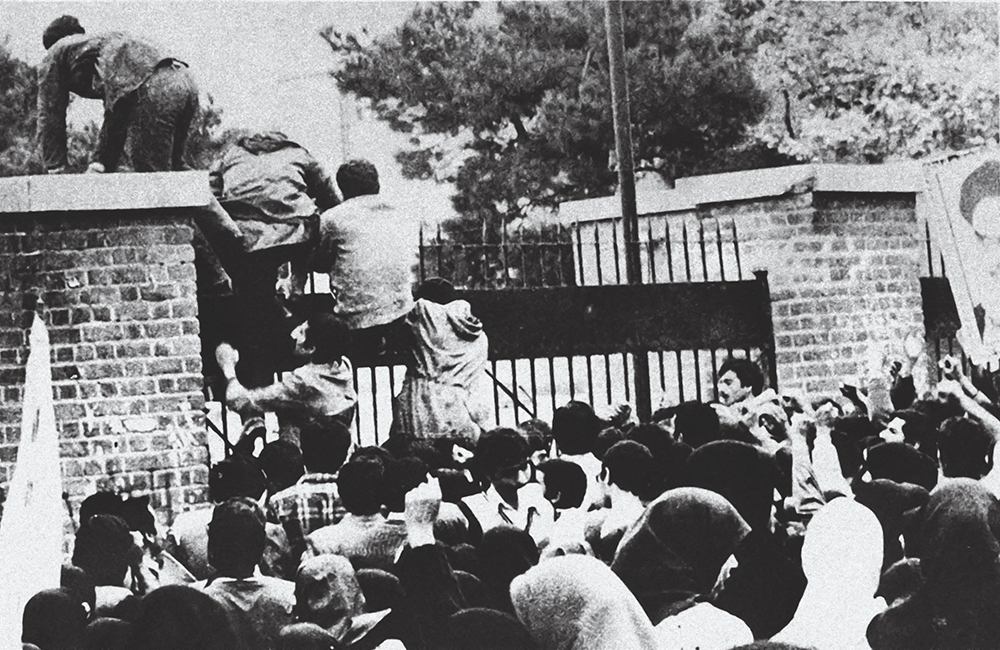

Storming the Compound

My connections to Iran go back to 1962, when my dad was assigned there with USAID and I was a college student studying history. The first Peace Corps Volunteers went to Iran that year; Rep. Donna Shalala was part of that group. I served there as a Volunteer 1964–66, and I went back a few years later to teach at Pahlavi University. My wife, Parvaneh, and I were married 53 years ago, and I’m proud to be part of a welcoming, well-educated, very kind Iranian-American family. The first language for both our children is Persian. My dream is to take our grandchildren to see Iran. A group of Friends of Iran Peace Corps people have been back multiple times. But I’m not welcome — because I remind them of a very black chapter in their own history.

As a foreign service officer, I volunteered to go to Iran in 1979. The Shah had gone into exile after nearly two years of protests. I arrived in August; in October, President Carter agreed to admit the Shah to the United States for medical treatment. On November 4, the embassy was overrun by 3,000 students and captured.

Had there been a functioning government in Iran, presumably they would have sent some help. To this day, I blame those who had the power to react and didn’t take the responsibility to do so.

November 4, 1979: the storming of the U.S. Embassy in Iran. “Despite the obvious dangers, our embassy had only minimal defense against a mob attack,” John Limbert wrote recently. “When that attack came, [Ayatollah] Khomeini not only did not condemn it, he praised the mob as agents of ‘a second revolution, greater than the first.” Photo by unknown photographer via WikiCommons.

For the next 14 months, we had no communication with the outside world beyond some heavily censored letters from our family. I was held in solitary for nine months. Usually what would happen is I would tell myself, if I can get through a day, that would be okay — then two days, a week, a month.

In July 1980, I did find out that the Shah had died. Then the Iran-Iraq war began, which was more important to them. They had grudges against Carter, but after he lost the election, that wasn’t so relevant. They had solidified their political position inside Iran. There was not much use to holding us anymore. On January 20, 1981, they put us on a plane to Algiers.

Ignore Previous Message

For the last 40 years, we have been insulting and threatening each other. We’ve come to the brink of war. In 2009, I was asked: “Would you come work with the Obama administration to see if we can change this way of dealing with each other — not necessarily to become friends, but just to break out of a pattern that has done nothing?”

As often happens in international politics, timing is everything. And the time wasn’t right.

President Obama used a phrase in Oslo that I have often used. He said, “I know that engagement with repressive regimes lacks the satisfying purity of indignation.” Most of us who have had the Peace Corps experience share this view, whether we like the Islamic Republic or not. And I do not. It’s a pretty awful regime, about as bad as you can get. But that’s not the point. The question is, What sort of policy should we have? What should we be aiming for? One day, we and the Iranians will be able to talk to each other. We got a glimpse of that in 2015–16. One day we may get there, and when we do, we will look back and ask: Why did we waste so much time hating each other?

There are voices within this country, both American and within the Iranian diaspora, calling for war. One is a strange, cultlike group, which has spread out its network in Washington: the Mujahadeen-e-Khalq.

There are voices within this country, both American and within the Iranian diaspora, calling for war. One is a strange, cultlike group, which has spread out its network in Washington: the Mujahadeen-e-Khalq, also known as the MEK. Back in the ’60s, they were a Marxist opposition group to the Shah. They have changed themselves into a cult, and using money believed to be from the Saudis, they have discovered what so many in Washington, D.C., have: Money can buy you anything. They have bought people on left and right — Newt Gingrich, Rudy Giuliani, John Bolton, Elaine Chao, Bill Richardson, Howard Dean. They would love to see a war, because they think that in the aftermath they could take power.

They present themselves as partisans of secular liberal democracy. Their real inspiration comes from the Khmer Rouge and James Jones. Most Iranians, who may well intensely dislike the clerics and their brutal, corrupt business, would hate these other people much more. They also murdered Americans in the ’70s. The problem is, these people are well financed, well organized, and have high levels of support. The U.S. Secretary of State sent out a notice in January 2020 to all embassies saying you should have nothing to do with this group. I saw that and said, “Wow, that’s progress!” The next day, he sends out a message saying ignore previous message. Who got to him?

I think a lot of steps that President Trump has taken vis-a-vis Iran have nothing to do with Iran — and have everything to do with his predecessor. If his predecessor negotiated an agreement, by definition that had to be a bad agreement.

But just because we get a new administration with a different philosophy doesn’t mean the Iranians are going to agree with us easily or quickly. That was certainly the case with President Obama. From the day of his inauguration, he sent out a clear message: We should be talking to each other. The Iranian reaction, for about three or four years, was “What’s the trick?” The other problem: We had President Ahmadinejad in Iran until 2013. He was toxic in this town. Didn’t matter if what he said was sensible or nonsensical. No one was listening to him.

There’s not going to be sort of a wake-up on January 21, 2021. It’s going to take patience, just like getting to the nuclear agreement — forbearance, listening, persistence. But there should be a determination to do things differently.