How service as Volunteers shaped careers in public health, teaching, and more — for Americans and Koreans alike

How service as Volunteers shaped careers in public health, teaching, and more — for Americans and Koreans alike

By NPCA Staff

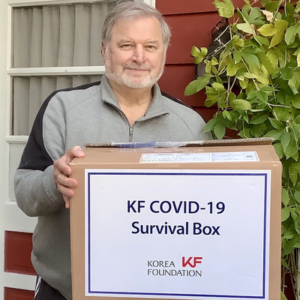

Photo: Survival box, delivered to Gary Krzic, President of Friends of Korea. Photo courtesy Gary Krzic

The gifts of more than 500 COVID-19 survival boxes to Returned Peace Corps Volunteers who served in South Korea inspired news stories across the country. Here are a few. As some note, the Korea Foundation, which sent the boxes, coordinated with Friends of Korea, the group of returned Volunteers, to find and thank them.

The Korea Foundation also created a video. A story about returned Volunteer Sandra Nathan in The New York Times, which also apperas in WorldView, drew hundreds of comments as well. Read those comments here.

“Korea taught me … and it gave me my career.”

Paul Courtright’s lifelong work in public health began when he traveled to South Korea as a Volunteer in 1979 to work with leprosy patients. Courtright “didn’t know anything about leprosy, once thought to be so contagious and incurable its victims were sent into isolation in leper colonies on islands and in remote places,” as John Wilkens writes for the San Diego Union-Tribune and Los Angeles Times. Actually, leprosy is treatable, and it does not spread easily. But, Wilkens writes, “Stigma still surrounded the patients in Korea, Courtright found when he arrived there after three months of Peace Corps language training. And he noticed something else — about 10 to 15 percent of the people were blind.” Accompanying patients to a hospital where an ophthalmologist treated them, Courtright “took what he learned back to his village of about 600 people, and then to other resettlement communities.”

After Peace Corps, Courtright earned a master’s at Johns Hopkins University and a doctorate in public health from University of California, Berkeley. For decades his work has been focused on health work to tackle preventable blindness, particularly in Africa. As Courtright told Wilkens, “Korea taught me many things, and it gave me my career.” Courtright and his wife, Dr. Susan Lewallen, also established the Kilimanjaro Center for Community Ophthalmology, with this mission to foster “high-quality eye care services provided by Africans for Africans.”

When Courtright received a box from the Korea Foundation, he emailed thanks to foundation president Geun Lee. Lee’s quick reply: “Though decades have passed, the country where you spent years of your cherished youth has not and will not forget that affection … We return it and will continue to pass it down from generation to generation.”

“Some hand sanitizer and a few masks.”

That’s what Kathleen and Bud Wright expected when they got word that the Korea Foundation would be sending a box to them in New Jersey. Instead, as the Times Herald-Record notes, “There were 50 KF-94 masks and antimicrobial copper glove sets. There was a good-quality blue nylon backpack, and a tin of red ginseng candy. There was a silk fan.” Also: “In a black velveteen case with a gold-colored clasp, tucked into silk pouches, were two sets of silver-plated chopsticks and spoons with a turtle design.” There were messages sent from Koreans via Instagram put into a booklet of thanks and well-wishes.

The Wrights served as Volunteers 1973–75, teaching English at Konkuk University in Seoul. Kathleen’s scholarship and teaching as a professor at State University of New York, Orange, took her around the world — including back to South Korea for research. She and other Volunteers also returned to South Korea in 2008 for a visit sponsored by the Korea Foundation.

Students and teachers: Seong Su Middle and High School, Chunhceon, 1971. To the right of Volunteer Dan Holt is his co-teacher Youngok Park; they co-authored the Methodology for Teachers guide used throughout middle schools. Holt went on to serve as TEFL advisor for the Peace Corps office in Seoul. Park succeeded him. Photo courtesy Friends of Korea

Full circle

Russ Dynes traveled to South Korea as a Volunteer in 1972, assisting at a health clinic in a small farming community in the southwestern region of Gochang. The crisis at that time: an outbreak of tuberculosis, he told the Newark Post. As part of his work, Dynes would accompany nurses on visits to the countryside. Post–Peace Corps, he went to work with the Delaware Division of Public Health on a lead poisoning control program. New Jersey is home for Dynes now. As the Post notes, the arrival of the gift box was bringing the journey of service full circle.

Speak your peace

When we at WorldView reached out to Sandra Nathan, she wrote: “The Peace Corps’ mission is ‘to promote world peace and friendship’ … I would love to hear from other returned Volunteers who are continuing their work to promote peace and friendship and interested in the campaign to achieve peace in the Korean peninsula.” About that, she adds: “I am working with a local U.S. organization, Women Against War, to support Koreans’ wishes for a peaceful peninsula and will also be lobbying my Congressman and Senators to co-sponsor a bill to formally end the Korean war.” No peace treaty was signed; an armistice has been in place since 1953. House Resolution 152 was introduced by Rep. Ro Khanna (D-CA) in 2019, calling for a formal end to the war. “An end to the war would help facilitate the negotiation of arms reduction and the denuclearization of the Korean peninsula,” Nathan writes, and it would facilitate “reunification of divided Korean and Korean-American families, people-to-people exchanges, humanitarian cooperation, and repatriation of service members’ remains.”