Another time, another place, another virus

Another time, another place, another virus

By Barry Hillenbrand

”Eradicating Smallpox in Ethiopia” is a hefty and important book that rightfully deserves an honored place on any shelf of serious books about epidemiology and public health. The book tells the tale of the work that some 73 Peace Corps Volunteers did in the 1970s with the World Health Organization’s (WHO) Smallpox Eradication Program (SEP), a massive project that ultimately eliminated smallpox from the world.

This serious story is served up with large dollops of nostalgia, humor, delightful tales of daring, and loads of information about fighting infectious diseases, which — as it turns out in these times of the coronavirus — makes the book very contemporary. Even useful.

By the early 1970s, WHO’s goal of eliminating smallpox around the world was nearly accomplished. The SEP had battled down smallpox in all but a handful of countries. Ethiopia was one where the disease had been stamped out in major population centers, but it still raged in the remote corners of the country where there were few roads and meager medical infrastructure. Peace Corps and the WHO agreed to send Volunteers into these remote areas to root out the disease.

In late 1979, Ethiopia — and the world — was declared smallpox-free.

This book is made up of essays by the Volunteers who served in the SEP, plus contributions from Dr. D.A. Henderson and Dr. Ciro de Quadros of WHO. Inevitably there is a bit of repetition in the stories of broken Land Rover axles, tent-invading ants, the administration of massive numbers of vaccinations in crowded market places, impassable roads, and parasite ravaged guts. But the sum is far greater than the parts. This is a rich narrative history of a wildly successful and difficult Peace Corps project. These guys — and, yes, they were all men — were what we ordinary Peace Corps Volunteers called “real Peace Corps.” Peace Corps staff called them “Super Vols.” And they were.

Edge of the Gishe plateau: from left, SEP team members Ali Abduke, Lewis Kaplan, Girma, October 1973. Courtsey Warren Barrash.

The program used classic public health tactics: Find the remaining cases of the disease via intensive search and surveillance of the far corners of the country, then isolate and contain the disease carriers behind circles of vaccinations. No need to vaccinate the entire population of the country (though in the end SEP administered more than 17 million doses), just areas around where an outbreak was taking place, to create a barrier against its spread.

Sounds easy, but it wasn’t. Ethiopia is the second-largest country in Africa, but at the time had only 5,000 kilometers of what might be generously classified as all-weather roads. Over 80 percent of the population lived more than 30 kilometers from these roads. There are highlands with 13,000-foot mountains and sweltering deserts that sit below sea level. And in between are endless gullies, gorges, escarpments, and ridges to traverse.

Logistics were a nightmare. WHO handed out new Land Rovers to many PCVs in the program; they carried supplies to the jumping-off points, loaded gear on mules and, if they were lucky, also rode mules up and down escarpments in search of smallpox cases. Once, when there were no mules to rent, a PCV suggested to WHO headquarters in Addis that WHO buy a couple of mules for SEP use. The request was sent all the way up to WHO’s Geneva headquarters, where it was denied. The Volunteer, disappointed but determined, ponied up his current month’s living allowance and bought a pair of mules himself, reselling them later after the project was finished.

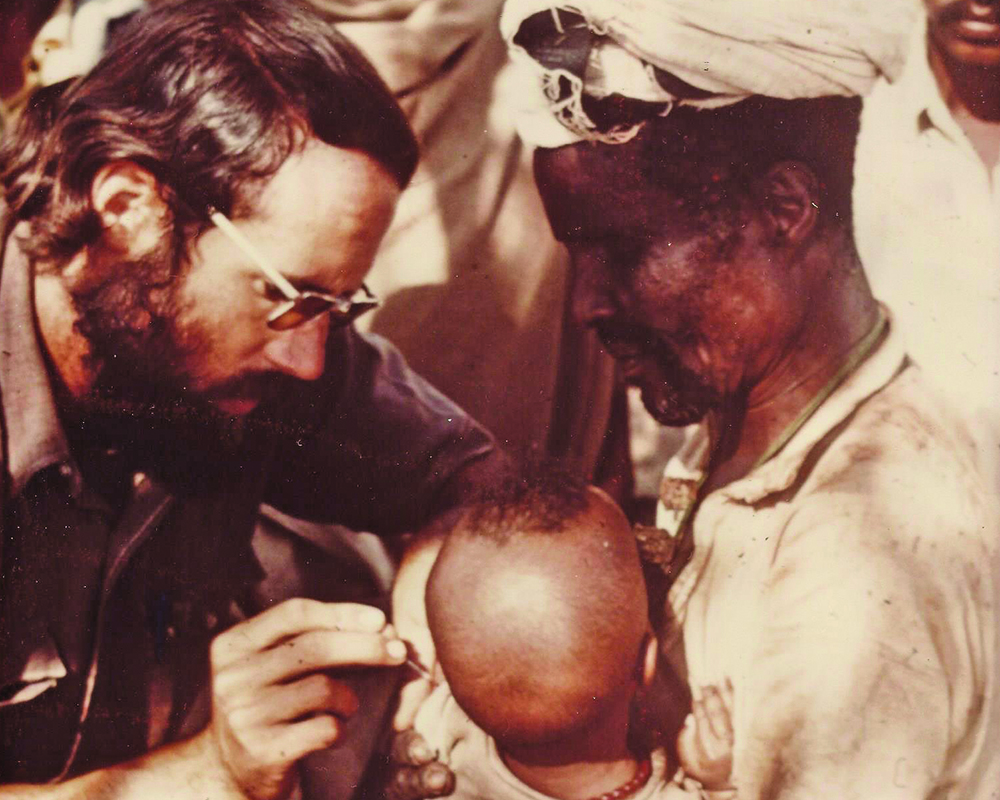

Gemu Gofa: A child receives a smallpox vaccination from Volunteer Michael Santarelli, 1973. Courtsey Mark Weeks.

Mostly they walked: hours and hours, from village to village over footpaths that took them to the far reaches of Ethiopia. They carried cards with pictures of smallpox victims, asking villagers if they had seen any cases. The PCVs hauled tents with them, but often they slept on the floors of regional health centers or, more often, in the mud tukul (round hut) of villagers who offered them welcome and shared food with them. The generosity and friendliness of these villagers — often the poorest of the poor of Ethiopia — was boundless and fills the PCVs’ writings, 50 years later, with a profound sense of admiration and affection.

While logistics were a major problem, the PCVs had to contend with other subtle and often more worrisome issues. Getting permission to vaccinate from local officials, in the form of a letter adorned with official stamps in that obsequious — and very essential — purple ink beloved by Ethiopian bureaucrats, was time-consuming and required great patience. Even with the letter from government officials in hand (some PCVs also carried a copy of a letter from Emperor Haile Selassie himself urging citizens to get the vaccination), finding cases and convincing people to be vaccinated was a laborious task.

Some ethnic groups in Ethiopia were more receptive to vaccination than others. The Amharas of Gojjam and the central highlands, for example, were cool to the idea of letting foreigners jab them with the special WHO-designed smallpox vaccination needle. They required extensive persuasion by the PCVs, even when smallpox was maiming and killing people in the villages. Other Ethiopians eagerly accepted these strange foreigners, mistakenly called “doctors.” In some places when word went out that vaccinations were on offer, hundreds of villagers showed up and pressed forward with such eagerness to get their vaccinations that it was difficult to maintain order.

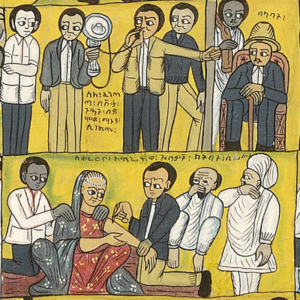

Market day: Senyo Gebaya, northwest of Addis Ababa in Gishe woreda (district), May 1974. Courtesy Warren Barrash.

As for that needle: It was a two-pronged affair, and each cost less than a quarter cent to produce. The bifurcated tip was dipped into a bottle of vaccine; a drop would stick between the forks. The vaccinator would then make multiple punctures in the skin of the person being vaccinated.

Some PCVs worked alone, mastering not only the difficult terrain and stubborn mules, but the mélange of languages and customs. Most traveled with Ethiopian coworkers — public health professionals often called “dressers” or “sanitarians.” They shared the difficult trails, administering the endless rounds of vaccinations. Often they were able to provide interpretation into the other languages of Ethiopia. And they were good company and became close friends with the PCVs. Stuart Gold writes: “The WHO and Peace Corps workers of SEP… did contribute to the eventual demise of smallpox in Ethiopia, but in fact, it was the nationals on the ground, the translators, the helpers, and the sanitarians who worked alongside us who deserve most of the credit. Without them, we would have been unable to navigate the nuances of the Ethiopian culture and traditions.”

In their individual essays, the PCVs unfailingly pay tribute to the two beloved and admired WHO leaders of the project: Dr. Donald A. (D.A.) Henderson, director of the WHO’s Global Smallpox Eradication Program, and Dr. Ciro de Quadros, the charismatic and tireless WHO epidemiologist in charge of field operations in Ethiopia. These two WHO professionals not only led the successful fight to eradicate smallpox in Ethiopia, but taught the inexperienced PCVs their fieldcraft. The book is dedicated to them.

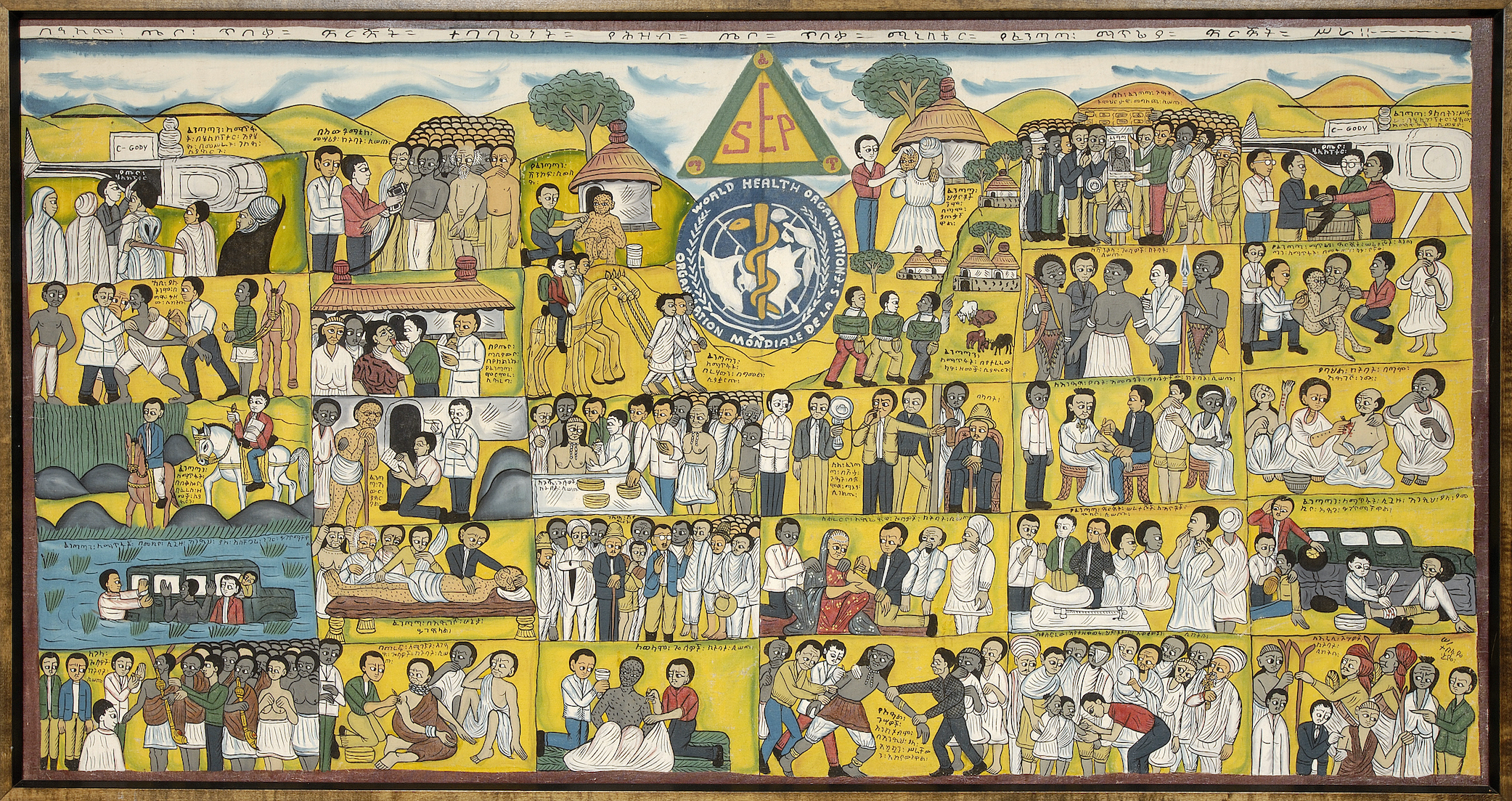

“The Smallpox Eradication Program in Ethiopia.” Mural by Ato Tesfaye Tave, 1975. Mural courtesy the Institute of the History of Medicine, The Johns Hopkins University.

By 1973, smallpox was on the run, even in remote areas, but Ethiopia was undergoing profound changes. A severe famine struck the country’s central highlands. A few PCVs left the smallpox project and began working in famine relief. In 1974 Emperor Haile Selassie was overthrown and an autocratic, communist-leaning government, the Derg, took power. Peace Corps withdrew from the country. WHO hung on, secured the support of the new revolutionary government, and ultimately finished the smallpox project using government helicopters and highly effective Ethiopian health workers, many of whom had worked with the PCVs. In late 1979, Ethiopia — and the world — was declared smallpox-free.

As for those young PCVs who had arrived in Ethiopia clutching their newly minted degrees in English and history and left the country after two years of service as battle-

tested public health workers, many of them returned to the United States to get advanced degrees in public health. Some even went to work again with WHO. Michael Santarelli, who once vaccinated Mursi warriors he encountered while traveling, participated in WHO’s smallpox eradication project in Bhola Island, Bangladesh, where the last recorded outbreak in Asia took place. Once a Super Vol, always a Super Vol.

Barry Hillenbrand was a Volunteer 1963–65 in Debre Marcos, Ethiopia, where he taught history at a secondary school. As a summer project, he gave TB test injections in the central market in Harrar, Ethiopia. After Peace Corps, Hillenbrand became a correspondent for Time magazine. His essay first appeared on PeaceCorpsWorldwide.org.

Eradicators and Contributors

Writing the book “was truly a group effort that required a bit more than five and a half years to complete,” says lead editor James Skelton. And, as he told the Houston Chronicle last year, “It became clear to me pretty early on that these guys in the field were heroes.” An attorney in Houston, Skelton knew the journals that most Volunteers kept could help provide raw material. But giving the material shape took work. D.A. Henderson provides the opening context with “Global Eradication of Smallpox.” Ciro de Quadros wraps things up.

Here’s the Peace Corps team, along with their years of service:

Warren Barrash (Malaysia 1970–72, Ethiopia 1973–74)

Gene L. Bartley (Ethiopia 1970–72, 1974–76)

David Bourne (Ethiopia 1972–74)

Peter Carrasco (Ethiopia 1972–74)

Stuart Gold (Ethiopia 1973–74)

Russ Handzus (Ethiopia 1970–72)

Scott D. Holmberg (Ethiopia 1971–73)

John Scott Porterfield (Ethiopia 1971–73)

Vince Radke (Ethiopia 1970–74)

Michael Santarelli (Ethiopia 1970–73)

Alan Schnur (Ethiopia 1971–74)

James Siemon (Ethiopia 1970–72)

James W. Skelton Jr. (Ethiopia 1970–72)

Robert Steinglass (Ethiopia 1973–75)

Marc Strassburg (Ethiopia 1970–72)

“Humanity’s Victory”

In May 1980, the World Health Assembly declared: “The world and all its peoples have won freedom from smallpox.”

For 3,000 years smallpox exacted a terrible toll; in the 20th century it killed 300 million. In May 2020, WHO Director-General Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus observed: “As the world confronts the COVID-19 pandemic, humanity’s victory over smallpox is a reminder of what is possible when nations come together to fight a common health threat.”

Key to success: an effective vaccine and a concerted effort to help people around the world. In strictly economic terms, the $300 million invested over a decade saves more than $1 billion a year in health costs. That does not measure the value of lives saved and suffering averted.